J.M.W. TURNER: REFLECTIONS ON THE PAINTER OF LIGHT

Reflections on the Painter of Light in his 250th anniversary year

5 minute read

To mark the 250th anniversary of J.M.W. Turner's birth on 23 April 2025 and the year-long Turner250 celebrations, we're sharing some of the highlights in the Ashmolean's collection of Turner's Oxford artworks, including his much-loved oil painting of Oxford's High Street.

Turner's Oxford highlights

View of the High Street, Oxford

South View of Christ Church etc. from the Meadows

Christ Church College, Oxford

Inside View of the Hall of Christ Church, Oxford

A View of Worcester College

A View from the Inside of Brazen Nose College Quadrangle, Oxford

View of Exeter College, with All Saints Church, from Turl Street

Inside View of the East End of Merton College Chapel

Corpus Christi and Merton College Chapel

A View of Oxford from the South Side of Headington Hill

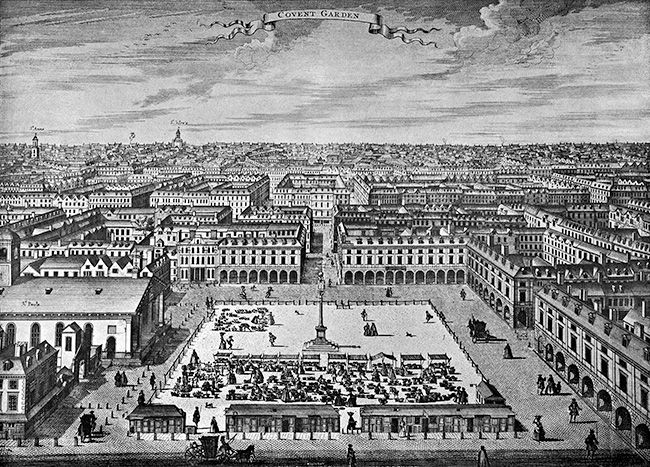

Covent Garden beginnings

Joseph Mallord William Turner was born in Maiden Lane in London on 23 April 1775, the son of William Gay Turner, a wig-maker and barber.

J.M.W. Turner, John Linnell, 1838, oil on canvas, NPG 6344 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Turner's earliest triumphs were reportedly exhibited in the windows of his father's barber shop in London's Covent Garden. With the promise he showed as an artist from a young age, it wasn’t long before Turner's works were on the walls of the prestigious Royal Academy, too. He began his studies at the RA at only 14 years old, and exhibited his first watercolours there after just one year of lessons.

Covent Garden looking north, c. 1720, from an engraving by Sutton Nicholls. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Turner's rise to fame

Today, the name Turner is almost synonymous with dramatic, atmospheric landscape paintings. Described by supporter and art critic John Ruskin as ‘the father of modern art’, Turner changed the game when he emerged on the 18th-century art scene.

In 1796, when he was 21 years old, he exhibited his first oil painting at the RA. The painting, ‘Fishermen at Sea’, caught the eye of many contemporary critics and set the foundation for Turner’s reputation as one of Britain’s most important artists.

The success of this painting put Turner on the radar of a number of wealthy patrons who supported his work, but also funded his travels and studies abroad. From 1802, he travelled widely throughout the UK and Europe during the summer periods, developing a particular affinity for mountain- and sea-scapes. He took most of his inspiration from what he saw on his travels, earning himself the nickname of ‘Prince of the Rocks’, as he was often found sketching outside, directly from nature.

Fishermen at Sea, J.M.W. Turner, 1796, oil on canvas © Tate

'Painter of Light'

As a young artist, Turner had quickly mastered the art of observing and recording the world around him. Over time, however, he began to pay less attention to minute detail and more to the dramatic, emotive effects of light and colour. Many of his works dealt with natural phenomena, from sunlight and moonlight, to snow, rain, storms and even fog.

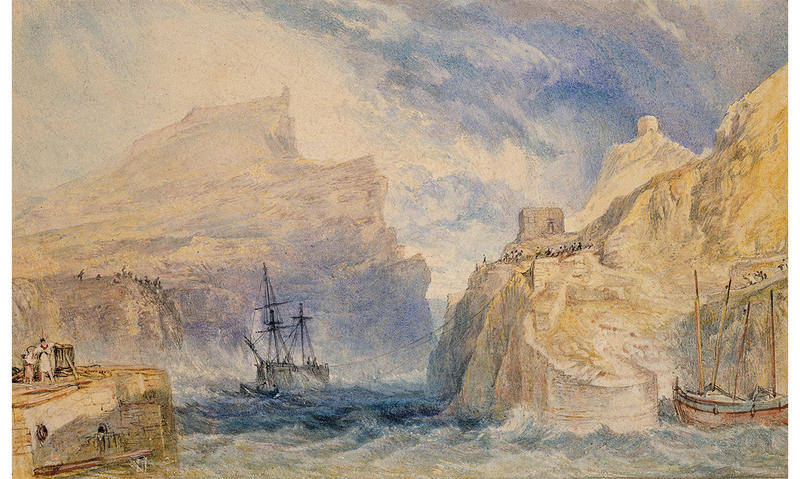

Boscastle, Cornwall, J.M.W. Turner, c. 1814, watercolour over graphite with pen & black ink © Ashmolean Museum

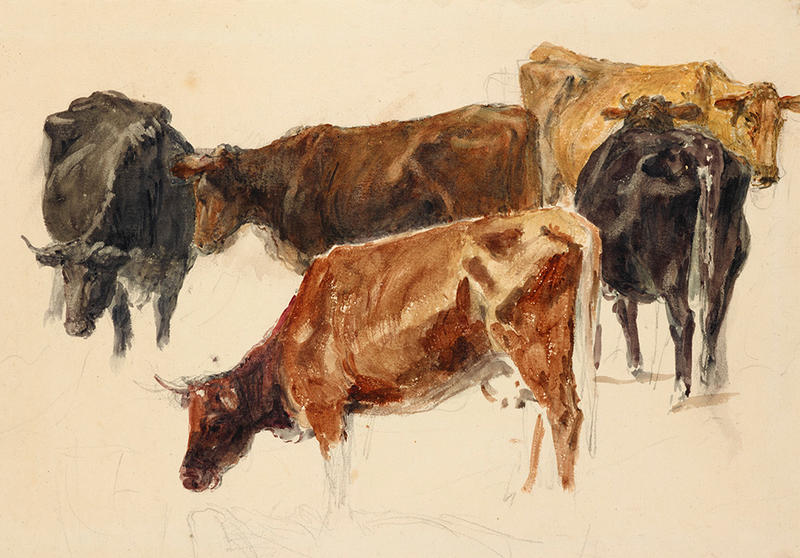

As he grappled with these ever-changing and often elusive subjects, the boundaries of traditional painting proved too limiting. His works became more and more expressive, with some bordering on abstract as form and detail became secondary to the mood of the scene. The unconventional methods he used to achieve his results ranged from scraping, blotting and scratching the surfaces of his watercolours, to using his fingers and even palette knives to create lively marks in his oil paintings.

His evolving style perplexed many of his critics and contemporaries. At a time when the grand classical tradition was very much in vogue, his style was anything but conventional. He was accused of ‘debasing’ the Old Master tradition, which embodied balance, detail and precision. In the 1840s, one of his more famous works was described as ‘soap suds and whitewash’.

But for every critic, there seemed to be a supporter who believed Turner to be a genius. Ruskin, by now an influential art critic of the time, described him as the artist who could ‘most stirringly and truthfully measure the moods of nature.’

Study of a Group of Cows, J.M.W. Turner, c. 1791 watercolour over graphite, with some scratching out, on wove paper © Ashmolean Museum

Sketch of Mackerel, J.M.W. Turner, 1830-1840, watercolour over graphite on Whatman Turkey Mill paper © Ashmolean Museum

Ruskin greatly admired the delicate study of mackerel above, particularly hailing the subdued iridescence of the fish portrayed. These had reputedly been brought in for dinner on one occasion by Turner's partner, Mrs Booth, with whom he spent time in Margate.

The artist's legacy

As his work continued to rise in popularity throughout the first half of the 19th century, Turner became increasingly private. Thought to be slightly eccentric and withdrawn, he had few close friends aside from his father, who helped him in his studio. He continued to travel and paint with fervour until he died on 19 December in 1851. At his request, Turner was buried in St Paul’s Cathedral, alongside Sir Joshua Reynolds and Sir Thomas Lawrence, whom he called his ‘Brothers in Art’.

Whilst Turner was capable of painting scenes in the fine detail that was favoured at the time, he chose to experiment and innovate. We can see now how Turner’s bold artistic choices inspired artists for years to come; his emphasis on light and colour paved the way for the Impressionists, while his departure from form and detail opened minds to the idea of abstract art.

Beyond his spectacular landscapes, which continue to stir emotion in the viewer almost 200 years later, it is his willingness to push the boundaries of art that keeps his work relevant and inspiring today.