ANSELM KIEFER AND THE ARTIST'S ROLE

5-minute read

By Xa Sturgis

Ashmolean director and co-curator of Anselm Kiefer: Early Works

Anselm Kiefer is one of the best-known names in German contemporary art and has become a towering figure of post-war art. His body of work fuses painting, drawing, photography, sculpture, woodcut and incorporates text.

The subjects and themes in Kiefer's uncompromising and extensive artistic oeuvre were shaped in his youth, as a young artist in post-war Germany.

In this article, Ashmolean director Xa Sturgis explores some of these recurring themes in our current exhibition, Anselm Kiefer: Early Works, featuring artworks from 1969–1984. The show reveals Kiefer's journey through figurative art, romanticism and expressionism; from his earlier, more intimate and colourful works to the large-scale, multi-media paintings we associate him with today, three of which open the exhibition.

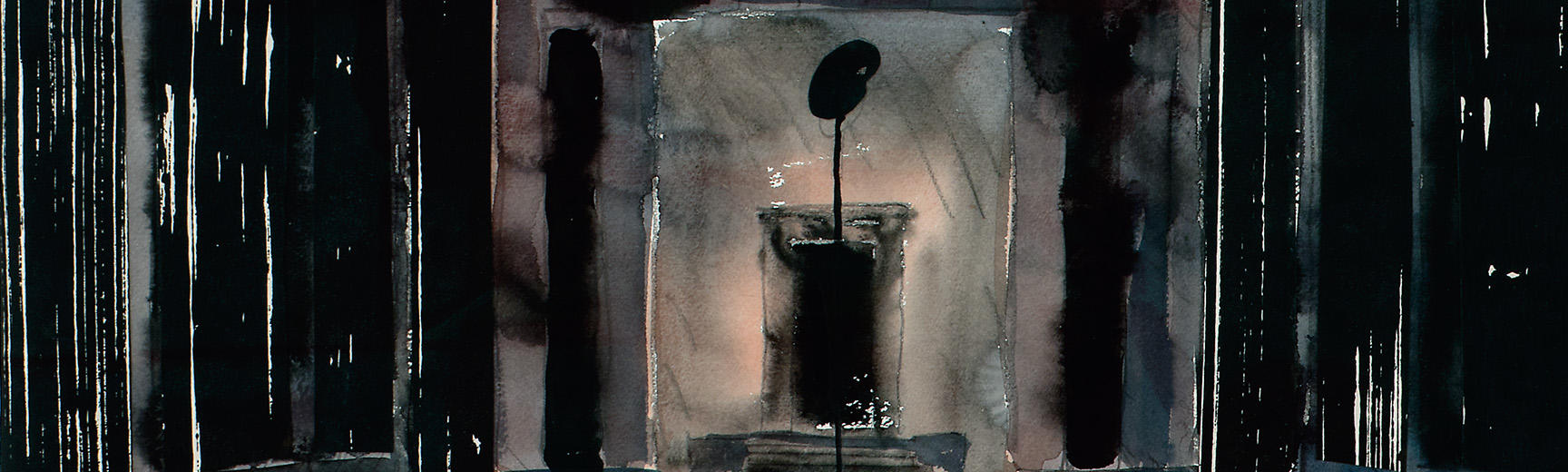

Entrance gallery in Anselm Kiefer's exhibition. Artworks © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Ashmolean Museum

The painter's palette

The poster image for the Ashmolean’s exhibition Anselm Kiefer: Early Works shows a winged painter’s palette rising through a star-studded sky towards a glowing celestial body.

Untitled, Anselm Kiefer, 1974, mixed media on paper, Hall Collection © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Adam Reich

This small dark painting on paper (dedicated to Elke Baselitz the wife of fellow painter, and one of Kiefer’s early supporters, Georg Baselitz) is among the earliest examples of Kiefer using the painter’s palette as a symbol of the artist in his work.

The winged palette, in particular, is a motif that Kiefer has used throughout his career and suggests the elevated if not transcendental role of the artist. For Kiefer, and in these images, the artist hovers between heaven and earth, able to ‘transform reality by suggesting new visions’ or ‘you could say that the visionary experience finds its way to the material world through the palette.’

There is no denying Kiefer’s ambition in his claims for the role of the artist, but at the same time his images of palettes often undercut such lofty optimism. Even in this transcendent image there is the suggestion that this ambitious palette might be flying too close to the sun and, like Icarus, may soon be plunging earthwards.

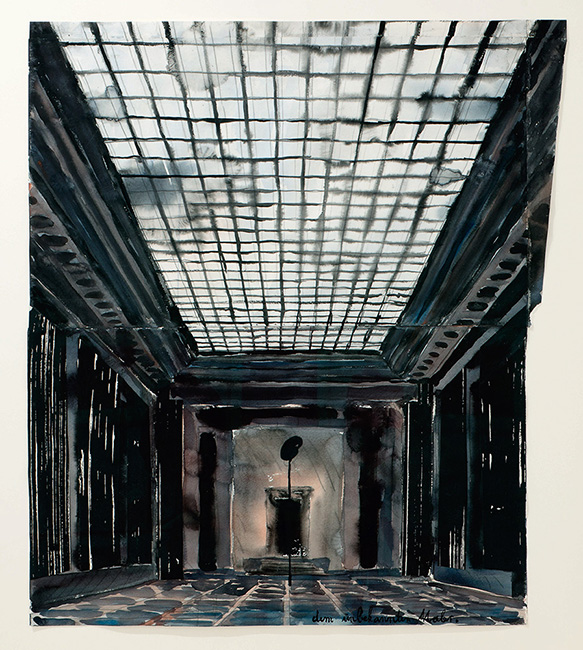

In Innenraum (Interior), one of the later works in the exhibition, a silhouetted palette stands in the centre of an empty Nazi-style building.

Innenraum (Interior), Anselm Kiefer, 1982, watercolour & graphite on paper, Hall Collection © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Steven Brookes Studio

The work is inscribed with the words ‘dem unbekannten Maler’ or ‘To the Unknown Painter’ and we are unclear if we are looking at a monument or a sacrifice and whether the painter is hero, villain or martyr.

The role of the artist in a post-Nazi world

Kiefer’s frequent use of the painter’s palette is an obvious reflection of the fact that one of his abiding preoccupations is the role of the artist in society. It is no surprise that a young man setting out on an artistic career should be concerned with what it is to be an artist. But for Kiefer the question was particularly pressing because of the German post-war world into which he had been born.

Kiefer was born in 1945, the last year of the Second World War, into a defeated Germany that had just lived through the horrors of the Nazi regime in which so many citizens were implicated or complicit. In the immediate aftermath of the war and the genocidal murder of six million Jews, the predominant response in Germany was silence.

In the realm of the arts there was also a retreat – a prevailing sense that the horrors of the Holocaust were too huge to be addressed, a view encapsulated most famously (although slightly misleadingly) in the Adorno’s contention that ‘after Auschwitz, to write a poem is barbaric.’ In the visual arts the predominance of abstract art perhaps reflects a suspicion of representational art, both as inadequate to the challenge of responding to the monstrosity of the Nazi project, but also because the Nazis themselves had championed realist painting.

The young Kiefer challenged both these stances head on in ways that shocked his contemporaries and retain their ability to shock and disturb today.

In his large painting, Heroic Symbols: Self Portrait, Kiefer shows himself wearing his father’s old army Wehrmacht overcoat delivering the Sieg Heil salute, a gesture that was illegal then and remains illegal in Germany today.

Heroic Symbols, Anselm Kiefer (self portrait), 1970, acrylic & charcoal on wood panel, Hall Collection © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Adam Reich

The painting is related to a group of deliberately provocative works – photographs and paintings – made between 1969 and 1971, but to which Kiefer has revisited throughout his career. In all of them Kiefer shows himself alone – often explicitly isolated – performing the salute. His purpose remains deliberately ambiguous, but was fundamentally to confront the German past and in doing so to insist that forgetting is not an option.

Confronting the Past wall in Gallery 1 of Anselm Kiefer's exhibition. Artworks © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Ashmolean Museum

To quote the artist ‘If we don’t remember what we have done, we will do the same thing again.’ His project was also a questioning one – an attempt to put himself into the shoes (or the coat) of his parents’ generation and to try and understand how they were swept up by Nazi ideology, while at the same time questioning how he would have reacted himself. In Kiefer’s words this was ‘a real working through of German History. You have to inhabit it to overcome it.’

How to paint

At the same time as Kiefer was confronting the Nazi past in these aggressively confrontational works, he was also struggling with the question of how to be a German representational, figurative painter engaged with and responding to the art of the past in a post-Nazi world.

A curious and not entirely successful series of works including the explicitly titled ‘How to paint nudes’ take an apparently humorous approach to the question, adopting figures from popular American ‘how to paint’ magazines, positioned in front of Alpine landscapes while an artist’s palette once again hovers ambiguously in the foreground.

How to paint nudes, Anselm Kiefer, 1974, oil on burlap, Hall Collection © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Adam Reich

At the same time, Kiefer was painting a series of deceptively simple and beautiful landscape watercolours that will, I think, be the biggest surprise to visitors who only know Kiefer through his more recent monumental, multi-layered paintings and sculptures. But even the most innocent-looking landscape runs the risk of contamination by the Nazi past.

Among the most beautiful in the exhibition is Wald (Forest) which can arguably be read as a simple view of the woodland in the mountainous region of the Odenwald, where the young Kiefer moved with his wife Julia and young son in the early 70s.

Wald (Forest), Anselm Kiefer, 1973–74, watercolour on paper, Hall Collection © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Adam Reich

But the motif of the forest is one to which Kiefer has frequently been drawn for its mythical and legendary associations with Germany and German national identity, associations that were exploited and championed by the Nazi regime.

More explicitly perhaps the landscape inscribed Die Etsch (the German name for the river Adige) is dotted with wounds, while its title would have unavoidably reminded a German audience of the first verse of the National Anthem sung between 1922 and 1945 and banned after the war. This spoke of Germany extending ‘from the Adige to Belt’ before proclaiming ‘Deutschland uber alles’ (Germany above all).

Die Etsch (The Adige), Anselm Kiefer, mid-1970s, watercolour, gouache & ink on paper, Hall Collection © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Mark-Woods.com

Reclaiming German culture

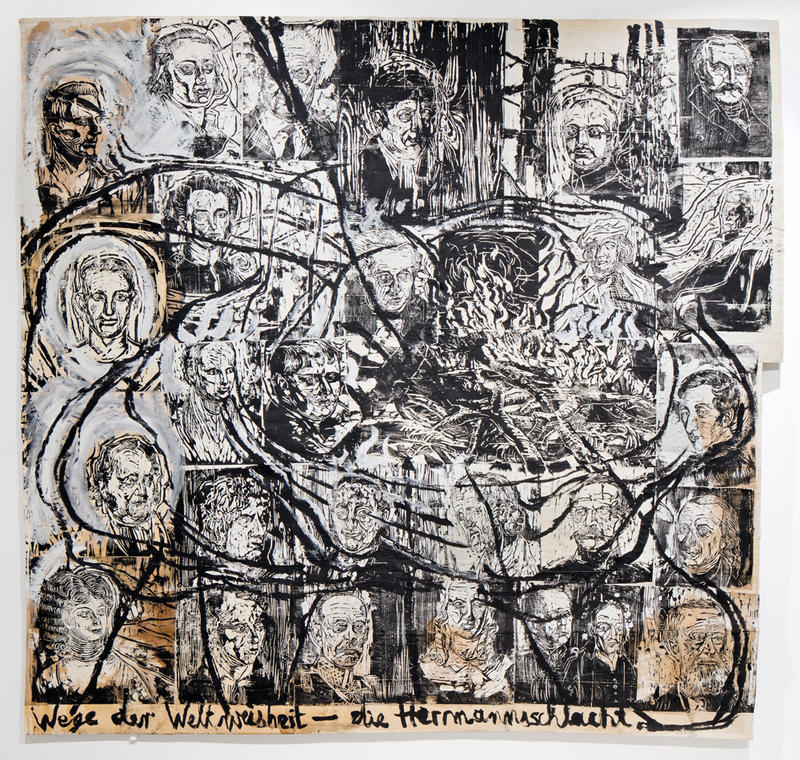

If Kiefer suggests that the German landscape has been contaminated by its use and abuse at the hands of the Nazis, this is even more obviously the case when it comes to German culture. An abiding concern for the young Kiefer (and indeed throughout his career) is the question of whether and how German national legends, mythology and culture can be reclaimed from their use, adoption and championing by the Nazis. In his ambitious composite woodcut, Ways of Worldly Wisdom: The Battle of Hermann, Kiefer assembles a collage of woodcut portraits of German historical and cultural heroes.

Wege der Weltweisheit – die Hermannsschlacht (Ways of Worldly Wisdom – The Battle of Hermann), Anselm Kiefer, 1977, woodcuts on paper laid down on synthetic fabric, Hall Collection. Courtesy of the Hall Art Foundation © Anselm Kiefer Photo: Roman März

Many of the portraits are copied from a book published in 1935 called ‘The Face of the German Leader’ (Das deutsche Führergesicht), which started with the legendary Germanic hero Arminius or Herman, referred to in Kiefer’s title, who defeated the Roman legions in the Teutoburg Forest and ends with Adolf Hitler.

Kiefer does not include Hitler’s portrait in his work, but his implied presence within this pantheon of German cultural heroes has the capacity to taint them all and by extension all of German culture and history. Even Kiefer’s choice of medium is not neutral. The woodcut is perhaps the art form most closely associated with German culture, from the woodcuts of Dürer to those of the Expressionist artist of the early 20th century. The works of the former championed by the Nazis, and those of the latter condemned and burned. In the centre of Kiefer’s work a fire also burns, a symbol of both destruction and purification, of censorship and martyrdom and of death and rebirth.

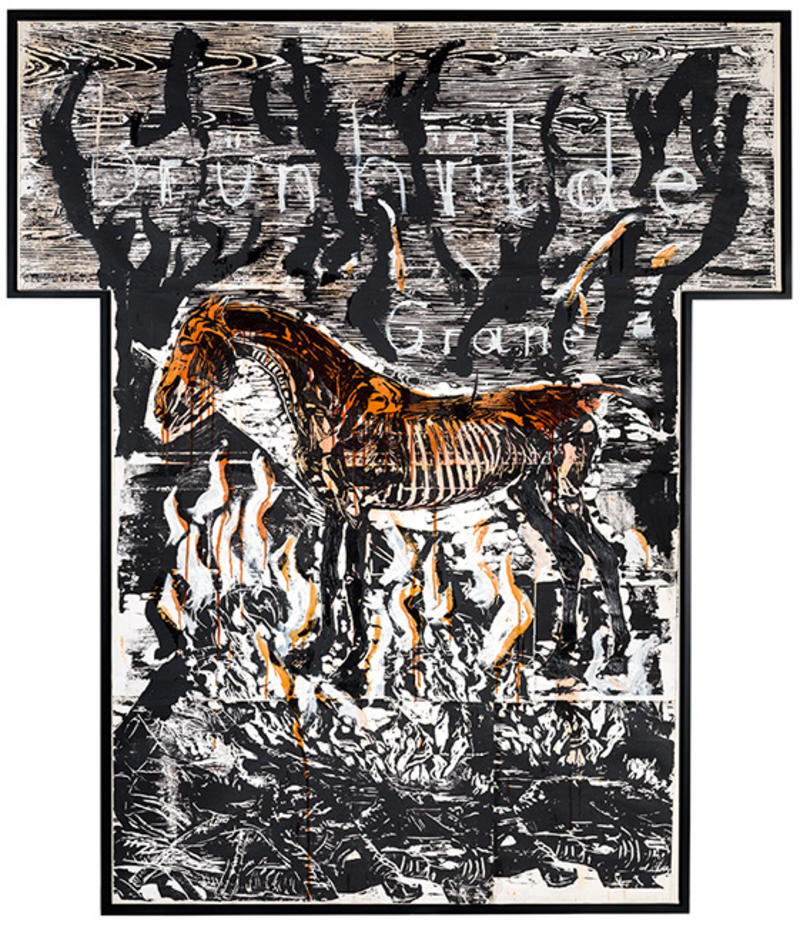

The fire or the pyre recurs in another spectacular woodcut in the exhibition, Brunhilde Grane.

Brunhilde Grane, Anselm Kiefer, 1978, collage of woodcuts on paper with acrylic, Hall Collection © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Arthur Evans

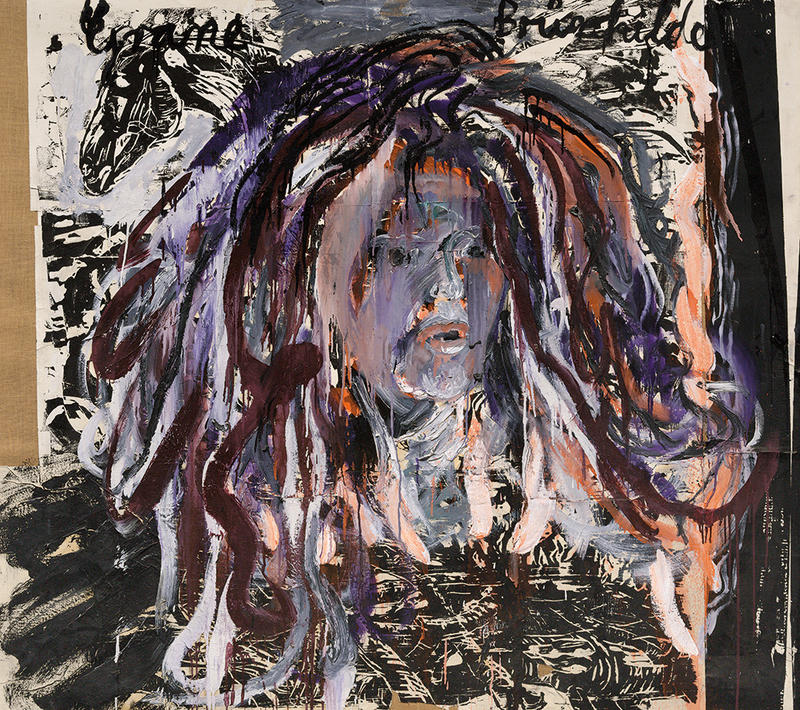

Brünhilde (Brunhild), Anselm Kiefer, 1981, oil & woodcut on paper laid down on burlap, Hall Collection. Courtesy of the Hall Art Foundation © Anselm Kiefer. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging

Grane was the horse of the warrior queen Brunhilde, famous from Wagner’s epic opera cycle, which is perhaps the most famous great work of German culture infected by its adoption by the Nazis. In the Ashmolean exhibition, Kiefer's collage of Grune is displayed next to his expressive painting of Brunhilde herself (above right).

Kiefer’s bold reclaiming of Wagnerian iconography does not exonerate Wagner, but does I think make the claim that art has a life beyond the meanings it is given at any single time or place: that the artist can, like Kiefer’s palette sprout wings and escape time and place.

Palette mit Flügeln (Palette with Wings), Anselm Kiefer, 1978, oil, acrylic & shellac on burlap, Hall Collection. Courtesy of the Hall Art Foundation © Anselm Kiefer Photo: Roman März

In Kiefer’s early works we see an artist with huge ambition, and growing certainty and confidence, find his voice and his purpose.