OUR MUSEUM: OUR VOICES

Each year, we hand over Museum exhibit labels to a new group of collaborators.

Look out for labels that are up around the Museum.

Part of the beauty of an object, or a museum collection, lies in its capacity to respond to more than one gaze and to unlock more than one story. The Ashmolean is committed to hearing and telling as many of those stories as possible. We want to discover what it means to be an Ashmolean for All.

Virtual exhibitions of past and present projects are available to view below.

OMOV 2023

Muslim students from Queen Mary University of London brought their faith and their personal backgrounds to their responses to the collection. Look out for labels around the Museum.

Medical students have also added their own interpretations on pale blue labels to match their surgery scrubs.

To find out more, email us at omov@ashmus.ox.ac.uk

The personal responses of local young people aged between 16 and 18 shone a new light on our collection.

Created by University of Oxford students, these labels – which appear in the Museum galleries – were written from personal experience as well as expertise, with participants considering their ethnicity, gender and sexuality in responding to the collections.

What do you think we should do next?

The Ashmolean is a public museum, a museum for Oxford, a national and a global museum. Over time we want to include and amplify more (and more diverse) voices, hear other stories and learn new ways of looking.

Get in touch with feedback and suggestions to omov@ashmus.ox.ac.uk

In winter 2019/2020, the University Engagement Programme at the Ashmolean Museum, funded by the Mellon Foundation, kicked off a new project, Our Museum, Our Voices. The aim was to amplify a range of diverse voices from amongst those with a stake in the university collections. A group of 24 students from the University of Oxford, who answered a call seeking collaborators, were chosen to participate in workshops over the course of the spring term. They wrote new labels for objects on display in the galleries, considering both their academic expertise and their ethnicity, gender and/or sexuality in responding to the collections.

We know that objects can bear many stories and convey a range of meanings; mute items become eloquent and resonate with varied perspectives. We also know that museums are not neutral: the stories that are told, the objects that have been collected are a product of choices and privileges, sometimes made over centuries. This can affect who feels welcome in a space, who can see themselves reflected back in the exhibits. The project group wished their interpretations to resonate with people from within their communities, and seek to broaden the understanding and experience of those outside them. They wanted to invite visitors to look again through their eyes and hear their voices in conversation with the object and the existing displays. The project took the form of a series of three workshops with the group. Scheduling was tricky, with Oxford students very busy in lectures, tutorials and classes, but we managed to work with portions of the group each time and kept in touch digitally. In the first workshop, we discussed what a label is, what it does, and how labels have affected each of us. Quiet at first, conversations soon developed in small groups, and spilled over into our exploration in the Ashmolean’s galleries to see what makes A Good Label.

In the second workshop, we considered the design and interpretation style for the labels, working with the Museum’s Head of Design, Graeme Campbell, and Interpretation lead Natasha Podro. With Graeme we also discussed how we would present ourselves visually as a group, while acknowledging the individuality of experience and voice behind the new texts. Natasha challenged the group to think about who the audience would be, what kind of relationship they wanted to build with them, and how we could move away traditional label formats to something more playful and diverse.

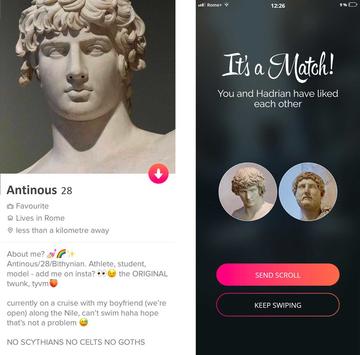

The tour of the museum from the first workshop also started the group ruminating on which object they would each like to select for a new label, and this workshop gave another opportunity to visit favoured galleries and have another look. Greco-Roman sculptures of Hermaphrodite and portraits of Antinous, Hadrian’s young lover, proved popular, along with objects from South Asia, pre-Raphaelite art, and more.

That left plenty to do in the final workshop. With objects chosen and draft texts submitted in advance, each student had the chance to work on their label further, one-to-one, while the rest of the participants broke into three groups to decide the final design, develop a leaflet, and to brainstorm ideas for an online platform. Ellie Field, Ashmolean web content editor, showed the group what could be done using video and social media promotion, as well as how best to provide information on part of the Ashmolean website dedicated to the project.

Texts, chosen signatures or pseudonyms, design briefs, and launch ideas were all submitted by the end of term, and then it was just over to us in the museum to make it happen…at which point we were sent home, locked down, and furloughed. Disappointed at first, we’re really delighted that we could return to this and redouble efforts to make sure that group’s work gets out there as soon as possible. The new labels are thought-provoking, funny, atmospheric and moving, and provide new contexts in which to think about the objects and their current interpretations.

The decision to work in the first instance with University of Oxford students was deliberate: this is a museum for the university as much it is of the university. It is fitting that those within this institution have contributed to what is displayed and feel some stake in it. Yet, the Ashmolean also has a wider outlook, to Oxford and to the world. We hope this will be the first tranche of a rolling project, working each year with different communities, in the University and across the city, with the aim of extending our shared ownership of this extraordinary place, all under the Our Museum: Our Voices umbrella.

This is the not first time that the Ashmolean and its sister museums in the University have done something like this. The ‘Out in Oxford’ trail, launched in February 2017, and the Pitt-Rivers Museum’s Beyond the Binary project, have involved a range of partners from students and researchers to community activists. At the Ashmolean, the existing ‘Nice Cup of Tea?’ exhibit is a step towards looking critically at works on display and the Museum is committed to a long-term strategy called Ashmolean for All, which aims to broaden its audience by community collaboration and through equitable and inclusive policies on display and interpretation. Our Museum: Our Voices will be one of the most tangible outcomes of this enabling vision.

It is at the intersections of the various facets of identity that difference can be felt most keenly, and broad efforts are needed to offer equity of opportunity in a truly diverse and inclusive museum environment. The protests of recent months have further underscored the work we need to do. We hope that this project will promote understanding and inclusivity, and will show how much we all have in common as well as celebrating the diversity of our shared human histories.

Penny Coombe, October 2020

With thanks to the project team in the Ashmolean (Natasha Podro, Jim Harris, Graeme Campbell, Ellie Field, and Sarah Casey – particularly to Natasha and Jim for their valuable comments on this piece), and to all of our amazing participants.

OUR MUSEUM: OUR VOICES 2021

Online Exhibition

Bright orange exhibit labels, written by local young people between 16 and 18 years old, were installed in the Museum, alongside objects chosen by the writers themselves exploring the Ashmolean’s online resources while the Museum was closed during lockdown.

A virtual exhibition of these objects, and their new labels, can be found below.

Aert van der Neer, Winter Landscape with Skaters on a Frozen River, from Gallery 45, Dutch Art, L1074.1

What’s the Point?

Not everything has a practical use. A picture, for example, serves no purpose but to entertain, to tell a story, to make a statement – about society or maybe about the painter themself.

This painting tells a story about my home country, the Netherlands, ice skating over the frozen lakes of the Northern Provinces.It has no use; but functionality was never a necessity. Why should it be today?

Buster Van der Geest

Paulus Willemsz van Vianen, Ewer WA2013.1.163, from Gallery 54, Wellby Collection

Confidence

Opulence and myth have always gone hand in hand: gold, lapis, mer-people.

Mermaids wait for their handsome mortal to sweep them off their tails; but this merman is not waiting, vulnerably sitting out of water unfazed as he plays by the lapis pool, his split tail lodging him on the ewer edge.

The merman knows he’s unique. His counterparts are silver; he is gold. They slip in and out of the waves, where he stands out like a ruby on the collar bone of a milkmaid.

Flora

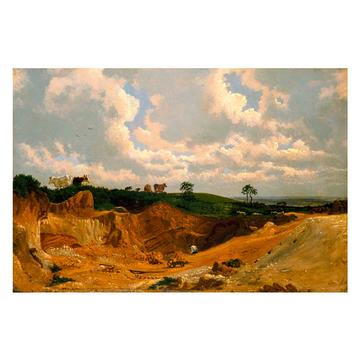

William Turner, Gravel Pit on Shotover Hill, WA1942.61

The Cost of Civilization

Although unable to see his expression, to me the leaning figure appears tired and isolated, surrounded by the world of work, oblivious to the beauty of nature outside the pit. He’s positioned in the middle - perhaps reflecting the importance we tell ourselves we have as humans - yet my attention was first drawn to the tranquillity of the untouched land which is (ironically) above him. It makes me question whether living in a man-made world of ‘enlightenment’ is better than simple animalistic pleasure.

E.N.

Bicci di Lorenzo, St Nicholas of Bari Banishing the Storm WA1850.26, from Gallery 42, Early Italian Art

A painting writes to its painter

Dear Bicci,

Scarves of doubt shroud my mind. Why are we so concerned with what people think of us? Why do we spend so much time bathing in anxiety as you bathe me in swathes of oil? We view ourselves as a collection of others’ opinions, and that infuriates me. Am I beautiful? Ugly? Demonic? Oh how I hate to be stared at. Tell me Bicci, how can a story be told by a corpulent mermaid, lost sailors and a not so modest God?"

Ella Grace Myers: An advocate for individualism

Nicolò Amati, The Alard Violin, WA1948.135 from Gallery 39, Music and Tapestry

Thank you

“I thank the Hill brothers for my collection

And Nicolo Amati for my frame

The Ashmolean for my preservation

Jean Delphin Alard for my name.”

I think if I was a violin, and my sole purpose was to play music, and that one purpose had been taken away from me, I would be extremely annoyed. But maybe it isn’t upset. Maybe it is contented to have played its final song. Maybe it is thankful.

Olivia

Pegasus, WA1888.CDEF.B438 from Gallery 56, Arts of the Renaissance

The Happy Horse

Child of Poseidon, foaled by Medusa, look at how joy surrounds the whole being and lights up the eyes. The pegasus soars in the sky with the birds, yet canters along the beach like wild horses, living between both worlds. What dreams it must have.

Mathilda Gatsby, Y13 Cherwell School, (cannot fly, nor run, but dreams

Johann Gregor van der Schardt, Foot after Michelangelo’s ‘Day’, WA2017.21 from Gallery 43, Italian Renaissance

Hopping along

A Foot! How careless to lose me, look how lavishly I’m dressed (although my toes need some work). Did you ever imagine losing a foot? How would you go about your day? Put yourself in my shoe. Do you know anybody like me?

Sincerely, an amputee. Mathilda. Y13 Cherwell School

Camille Pissarro, Jeanne Pissarro (Minette) Holding a Fan WA1952.6.2 from Gallery 65

Pissarro Was Kind

She’s young and she sits so still. Perhaps it’s the time of day, the thoughts she has, a lack of food. Imagine painting one of your own. Your child, someone you made. Your eyes are dark like hers. ‘Minette’ you call her. ‘Minette’ in a kind voice. A kind voice in a hard world. You’re known by virtue of your wisdom, a father to artists. Beneath worn out muscle you see good hearts beating.

Imogen E

William Dobson, Portrait of Prince Rupert, Colonel William Legge (probably) and Colonel John Russell WA2017.38, from Gallery 44, European Art

Searching for normality

What is normal? During a Civil War arguably there is no such thing. Is it having a drink with friends? Being in the company of a canine companion? Over the past year we've fought our own battles: small and large. We've realised it's the small things that matter - even a simple gesture like laying out this fresh tablecloth. Here are the faces behind the battles, the strategies, the conflict. Leaders doing what is expected of them. But here, they’re just trying to recreate normal - whatever that is.

Abigail Barrett

William Holman Hunt, The Afterglow in Egypt, WA1894.3, from Gallery 66, Pre-Raphaelites

The Afterglow in Egypt

This ethereal girl never saw this painting. Perhaps if she did, she would have despised it the second she saw it.

Or perhaps, she would not have been so reluctant to model for the strangely dressed painter, with his poorly pronounced Arabic. Perhaps, she would have been impressed that he was able to transform her into something divine, using only his memories and careful brushstrokes to be seen through your eyes.

Kirsten Nsendu

Teapots: WA1957.24.1.56, WA1957.24.1.858, WA1957.24.1.306 from Gallery 40, European ceramics

Tea

Tea. A uniting experience? We have all been offered tea in times of stress or when we need comforting. It is a ritual. An invitation for companionship. ’Do you need some tea?’

Rich in culture and roots but also steeped in cultural divisions, is the reality of tea more murky? And far less warming?

Aibh

Gold coin of William III, 1701, HCR 8158, to be temporarily installed in Gallery 55, alongside the Godolphin Gold Cup.

Not just a pretty face

After 320 years it’s hard to pinpoint the exact value of this coin today. But here is an idea what it could buy in 1701.

- 1 year’s rent on a shared bed in cheap lodgings

- Everything needed to supply a family of 5 for a month

- 576 loaves of bread

- 65kg of cheese

- 24 whole pigs

- 1234 rabbits

- 170 litres of beer

- 5.5kg of tea

- 28 pairs of woollen socks

Can you imagine a pair of socks costing almost as much as a pig?

Or 44 rabbits?

Rebecca Sadler

Intaglio gem set in an iron ring, eagle perching on an altar, ANFortnum.FR.163, from Gallery 13, Rome

The Ring

Take a look at this signet ring from Roman Thrace. The iron band is worn and pitted but the jasper face, with its roughly carved eagle, has defied time. Rings like this were often used to show off wealth and prestige and when used as seals, they identified their owner. Whoever wore this ring probably didn’t have much wealth to show off, nor many papers to seal, but almost 2000 years later, it is all we have left of them.

Dory Reynolds

Late Neolithic dagger, AN1927.4848 from Gallery 17, European Prehistory

Cutting Edge

Almost no experience in the life of a person in a modern industrial society quite mirrors the feeling of satisfaction that comes from knapping stone, watching it change shape as it’s bashed, knocked, sharpened. People were buried with daggers at their waists. This stone age blade is trying to be new, imitating the harder, more durable weapons of the burgeoning Bronze Age peoples - smelting and alloying metals, trading; communicating.

Braden

Mummy portrait of a Man, AN1922.240, from Gallery 27, Egypt Meets Greece and Rome

The beauty in falling apart

As time slowly chips away, we become but a memory connected to the items we once ruled over, defined by the things we possessed. Although it might appear that the plank captured the man’s beauty his image and memory remain at the cost of entrapment. He is only freed when the object itself is worn down by the whip of time, when all the bits of paint peel away to allow him to reclaim his true individuality and identity.

Lili n

Oil lamp with dome shaped lid surmounted by a bird, EA1983.27 from Gallery 31, Islamic Middle East

The Luxury of Light

The bird perched on top of this oil lamp guarded the stories and conversations illuminated by its soft glow. I imagine this bird would feel offended to watch as I thoughtlessly flick a switch. Perhaps a lightbulb more efficiently lights up a room, but the luxury of this lamp would have made whoever once owned it, cherish and notice the light that it created.

Emma Storey

Plaque depicting Prince Siddhartha and the Wounded Swan, EA2000.21 from Gallery 32, India from 600

Prince Siddhartha rescues a swan, shot by his brother Devadatta

Having been told that Buddhist monks kept very few items, I was confused as to why this plaque had been made. That was when I learned about punya, which means merit. Just as the story is used to show how the Buddha taught compassion towards all creatures on Earth, the act of carving its intricate details is one step further on the path to enlightenment of whoever created it.

Daisy

Camel, Tang Dynasty, EA2012.189 from Gallery 28, Asian Crossroads Orientation

Paul Jacobsthal’s Camel

Camels: slow, clumsy, and cumbersome - but this peculiarly clandestine camel escaped the wrath of the Nazis. Escaped with a flurry of papers and the slam of a briefcase, to Britain, to Oxford; but then to internment on the Isle of Man, until, liberated at last’ the camel greeted Paul home, never to be separated again. Now escape yourself, escape to the dusty distant origins of our camel, trace its path through time, leading up to this very moment, leading up to you.

Jake Peto

Gold posy ring AN2011.32, Gallery 41

Posy ring

At first this ring looks like something you might buy in a shop. But look closely. Can you see the tiny scratchings on the inside? The words read “Kindly take this for my sake”. Made in the 16th century, this posy ring is a token of love, a promise of undying affection. Though the owner may have died, the ornament hasn’t , an undying piece of a love story left for us to ponder.

Lola

Cast of the Nike of Paionios, from Olympia, CG.B.86, from the Cast Gallery

Eleutheria (Ancient Greek; ‘liberty, freedom’)

Strength. Nike stands, poised on the edge of flight. Wind caresses the cracks in the cast, and runs through her cloak. Sometimes Nike is stripped of her wings, trapping her within the walls of Athens – but here, her lost wings serve as a memory of freedom. As the Goddess of Victory, Nike was worshipped in hope of strength and speed. Her strength shines through even the cracks of this plaster – in her figure, her defiance, and her beauty.

Natasha

OUR MUSEUM: OUR VOICES 2020

Online Exhibition

Created by University of Oxford students, these labels – which appeared in the Museum galleries in 2020 and early 2021 – were written from personal experience as well as expertise, with participants considering their ethnicity, gender and sexuality in responding to the collections.

A virtual exhibition of these objects, and their new labels, can be found below.

Empty plinth in Greek literature section

Sappho

Sappho of Lesbos was a poet active during the 6th century BCE. Her poetry became incredibly important to European LGBTQ culture, with queer women exchanging violets (a reference to another poem) as a token of their secret love. The word ‘lesbian’, in its present meaning, is derived from her home island of Lesbos.

Natalie McGowan

Figure of Vishnu and Lakshmi,Gallery 32 India from AD 600, EA1965.161

Lakshmi: Goddess, devotee, teacher

Devotion and love, that is what counts. Lakshmi sits beside God, highlighting gender, class or creed are not of importance. She appears in her dual form of both the goddess of wealth and as God’s ideal devotee. Her raised position in this idol is a reflection of how she is widely celebrated in many Hindu traditions for her own powers and what she teaches others about devotion.

Meera Trivedi

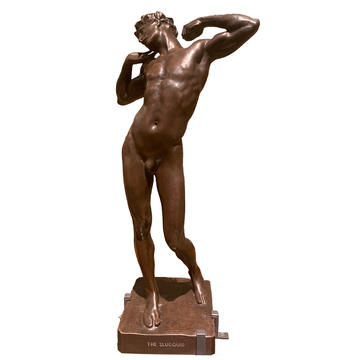

Frederick Lord Leighton, The Sluggard, bronze statuette, Gallery 66, WA1927.41

The Stretch

Look closer. This is the stretch of a lover, whom you have watched rise every morning. A pose that is known so intimately that the moment in time can be expressed in a bronze sculpture. Although never confirmed as homosexual, it makes one wonder, what caresses of both flesh, clay, and metal lead to this creation?

Richard Johnson (Canada)

Confirmed homosexual

Pre-Dynastic Comb AN1896-1908.E.955

Why the long teeth?

Combs are not just for removing tangles. Ever thought what the shape of a comb tells you about the hair texture of its owner? The tighter the curl, the longer the tooth.

Long-toothed combs have changed little in design for thousands of years, neither have the hairstyles they help create.

Spot the dreadlocks, sculpted plaits, braids and afros amongst the exhibits in the neighbouring rooms.

Rachel

MSc Teacher Education

Figure of Buddha beneath the Bodhi tree, Gallery 32 India from AD 600, EAOS.56

Buddha

Indian Buddhist literature describes the Buddha as a virile paragon of masculinity—he is said to possess 32 characteristics of a great man, including eyelashes as long as a cow’s and a penis hidden by a sheath. These attributes stand in contrast to Western constructions of idealised manhood. 19th and 20th century art historians accordingly saw the Buddha as asexual. This conception was reinforced by colonists’ characterisation of the Indian male body as effeminate.

Rhea Stark

The China to 800 Gallery at the Ashmolean

Uncharted Territory

It’s impossible to talk about China’s manufacturing past without mentioning what it has become today. Imagine a factory city as big as the City of London. Hundreds of thousands of employees living on site under execrable labour conditions in order to produce mobile phones for multinationals. Because of China’s regulated communications, alarmingly little is known about the people who occupy this factory city.

박미연

Medieval tile from Great Malvern showing sacrificed Jesus, Gallery 41, AN1967.672

On Jesus’s Vulva, and How the Mystics Found Him Sexy

Some medieval images of the crucifixion depict Christ’s wounded side as a vulva, giving birth to the Church. In this 15th-century ceramic wall tile from Great Malvern, however, Jesus is buff and masculine.

Blood spurts suggestively from his side. His mouth appears to be pouting.

The writings of the medieval mystics often presented the body of Christ in these ambivalently gendered and erotic ways. In this devotional tradition, Christ’s gender was so important, yet so unimportant. He simply existed to be adored.

George Haggett

Gay, trans PhD student

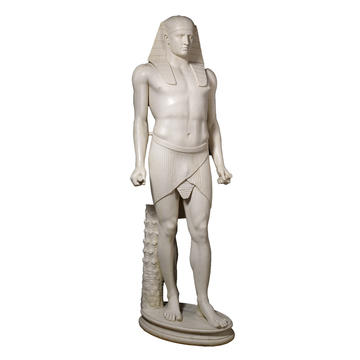

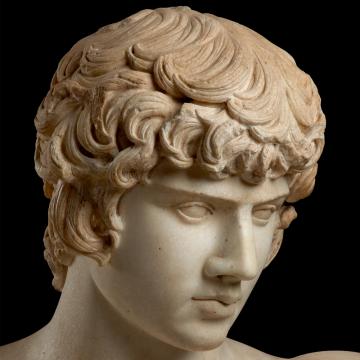

Antinous Osiris, Cast Gallery

The Emperor’s Boyfriend

Antinous was the lover of the Emperor Hadrian. They travelled extensively together across the Roman Empire until Antinous’s tragic death in Egypt. Upon his death, Hadrian had him deified, an honour saved for members of the imperial family. Past scholars have attempted to erase this, but it is undeniable that Hadrian and Antinous were lovers. Antinous should be remembered as being more important to Hadrian than his wife.

Aleks Fagelman

Non-binary Ancient Historian

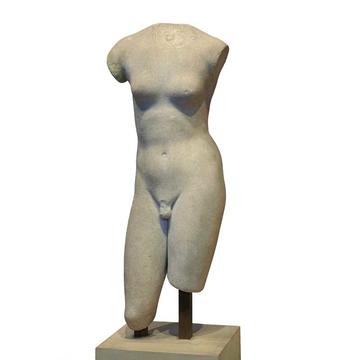

Hermaphrodite sculpture, Randolph Sculpture Gallery, AN.Michaelis 34

Hermaphroditus

Does this queer body offend you?

Sculptures such as this one show that transgender and intersex beauty has been worshipped since ancient times, and that there is a rich history to gender variance beyond the recent advances in trans rights. Hermaphroditus was the child of Aphrodite and Hermes, the Greek gods of sexuality. Born a man, the nymph Salmacis fell in love with him and prayed to the Gods to be united with him forever. Her prayer was answered, and their bodies became one, both male and female.

Jenny Scoones

Student

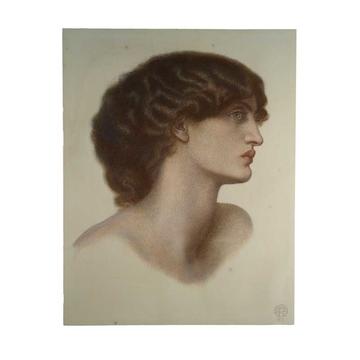

Perlascura (Jane Morris), Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Gallery 66, WA1939.4

Pre-Raphaelite Beauty (Perlascura)

What is it that makes Rosetti’s subject so striking? What is it that makes her beautiful? How does she differ from mainstream beauty standards? Pre-Raphaelite art is often recognisable for its depictions of androgynous beauty. Square jaws and thick necks characterise the works, blurring gender-boundaries and empowering gender variant people today. Whilst contemporary critics derided their art as ‘unmanly’, today the aesthetics of the pre-Raphaelites empower queer beauty.

Jenny Scoones

Student

Coconut cup and cover, Gallery 53, WA2013.1.208

“Civilising” the “Savage”

What’s the beauty in a humble coconut? In their curiosity cabinets, Renaissance elite captured its purported healing powers by blurring the boundaries between art and nature: transforming it into a boastfully magnificent cup. More sinisterly, this was meant to refashion the supposed “brutishness” of new-discovered lands into European ideas of “civility”, exploiting the cultural exchange which accompanied seapower developments. The cup’s stem, an indigenous archer, is unsurprisingly an exoticised illusion.

Sophie the Swamp Witch

Don't worry! Be happy! Sunshine reggae!

Ganesha, Gallery 32, EA1994.111

So quiet here! But you know that in Indian temples, you’d be hearing the tinkle of brass bells and gentle prayer chants. At home, Ganesha is surrounded by ripe bananas and cashews, fragrant clouds of incense and flickering lamps. Observe how this trickster deity is throwing his head to one side, ecstatically swinging his arms and raising his knee up to his belly. What music do you imagine he’s dancing to?

Sylee Gore

2019, MSt Creative Writing

Tara – Mithuna, India 2500BC – AD600 Gallery, EA1998.39

Spiritual Sex

All along the walls of the temple, couples engage in maithuna (sexual union). The place of the Gods welcomes the sexual energy of humanity.

Who stares at you, lovers? The disgustingly depraved, distracting themselves during worship, or the enlightened and spiritual seeking true unification with the universe, a natural purification of the mind? Carved out of stone, their transient bodies are fixed forever in an act of unified love and pleasure.

What do you suppose they see in their neighbours?

Tara Mewawalla

Excitable feminist literature fiend

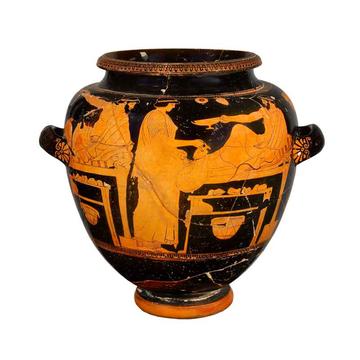

Athenian red-figure stamnos, attributed to the Copenhagen Painter, c. 500-450 BC, AN1965.127

Symposium

For the Greeks, sexuality was fluid and rarely thought of in a binary way. Homoerotic encounters were just as common as mixed-sex ones, and the art of the classical world reflects this. Male couples are often marked out by contrasting age - younger men converse with older, bearded ones. To our eyes, this scene looks like a platonic gathering. An Ancient Greek onlooker might assume the men depicted to be lovers.

Lauren Shirreff

Hermaphroditus, Cast gallery, CG.H.107

Sexual Assault in the Museum

With the victim’s genitalia only visible from certain angles, this depiction of sexual assault was intended as a joke for the Greek or Roman viewer. However in the modern day, the discovery that a sex partner is trans is still used as a legal defence of sexual violence in courts around the world, and trans women continue to suffer from high rates of murder and assault.

Should we present depictions of sexual assault in the museum? If so, how?

How can we challenge the transmisogyny (violence against trans women) and lack of respect given to gender non-conforming people in the museum and in our lives?

Naomi Clark

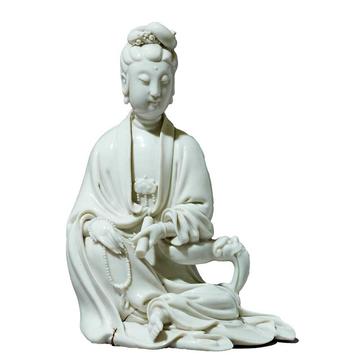

Seated figure of the bodhisattva Guanyin, China, Gallery 38, EA1982.2

Hand Signals: Seated Guanyin

Facial expression, clothing and symbols are the usual ways that Western statues speak. Buddhist imagery is different. Faces are often hard to read, while clothing and symbols follow complicated convention. Hands are always expressive though. For a viewer one thousand years later, the grace of this Guanyin's hand language speaks to us over a great distance and many centuries. It's a shame that only one hand is left.

Catherine de Guise

Seated Guanyin, EA1956.3285

White and Willowy: Seated Guanyin with raised knee

This beautiful white-robed woman appears to conform to conventional ideas of femininity. Actually, she retains elements of the male bodhisattva Avalokitesvara. Her flat, exposed chest and her raised knee were signs of masculinity that were missed by early European viewers. Today they reveal the eternal complications of gender.

Catherine de Guise

Ceramic sculpture of a women on a camel, Gallery 35, WA1967.28.100

What was the Orient?

Before the 19th century, Europeans knew little about specific Asian countries. Elements of the “Orient” depicted in Western art were consequently drawn from a range of Asiatic cultures including Turkey, China, Japan, India, and Algeria. Sometimes, these cultural motifs were also blended with European elements. Notice the European influences in the dress worn by the Chinese woman in item 19, for example. Try to spot this cultural ambiguity in other objects in this gallery.

Cherie Lok

Belvedere torso, Gallery 56, WA1961.5

Dear Torso,

Do you know how much you've been loved? 500 years of desire, countless reflections, recastings, pastiches. What was it in your pose, twisted, on the verge of action, that occupied the hearts of so many men whose own nakedness had to stay so covered? Who, like statues themselves, were unembraceable. You, who remain THE body, THE beloved, do you know Michaelangelo refused to fix you?

Max Tristan Watkins

St Catherine of Alexandria, Vittore Crivelli, Gallery 43, WA1899.CDEF.P27

Who's the fairest of them all?

Saint Catherine remains a mystery but is remembered for her heroic virtue, intelligence, beauty and royal birth. She was supposedly born in Alexandria, Egypt, which may seem surprising given her ghostly, white skin. Why did Crivelli do this?

Whiteness has become emblematic of beauty, purity and class, acting as both a product and driver of the erasure of non-Western cultures. 500 years after Crivelli, and diversity is still lacking, eurocentric beauty standards dominate – has anything really changed?

Vaishna Surjid

History Undergraduate

Christ among the Doctors by Jacopo Bassano, WA1949.5

Odd one out?

Who is the figure on the left? Is his darker skin a reflection of his social status or ethnicity, or even both? Ultimately, we can’t be sure but the ambiguity speaks volumes.

In this entire gallery, this is the ‘darkest’ figure we can find. Regardless of his identity, he serves as a poignant reminder of the historic lack of BAME representation, especially in European histories, where such communities were and still are marginalised.

Vaishna Surjid

History Undergraduate

Box lid depicting a kinnara couple, Gallery 12, EA2013.38

Kinnara: Eternal Lovers

‘We are everlasting lover and beloved. We never separate. We are eternally husband and wife; never do we become mother and father. No offspring is seen in our lap. We are lover and beloved ever-embracing.’ – Ghosh, S. (2005). Love stories from the Mahabharata, trans. P. Bhattacharya. New Delhi.

In this quote from the Mahābhārata, an ancient Sanskrit poem, the Kinnara describe their eternal love. Kinnara were mythic creatures – sometimes half-human and half-bird, sometimes half-human and half-horse – who lived with their lovers high in the Himalayas.

Ayesha Purcell

Bisexual British-Pakistani from Liverpool

Lid or palette with the drunken Heracles supported by two female attendants, Gallery 12, EA1993.24

Two women carrying a drunken Hercules, probably from a woman’s dressing room.

We are in control here. Outside of this space, men dominate: our voices are silenced, intentions ignored.

But here, among soft clouds of perfume, the echos of women’s voices, and the clatter of makeup being mixed; we have power.

Even Hercules, icon of masculine strength and power, is reduced to stumbling helplessness. Whilst the women are clothed, his body is exposed; they stand upright, he slumps. This time, the strength is all ours.

Ayesha Purcell

Bisexual British-Pakistani from Liverpool

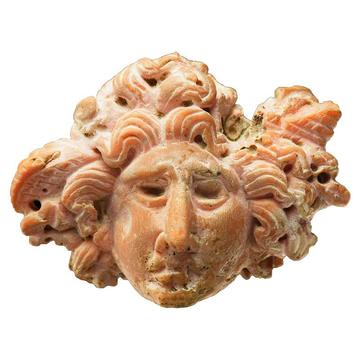

Head of Medusa, Gallery 12, EA1993.19

Do remember me? Do you recognise my hair, writhing, twisting? You might have seen me before, holding up Greek temples, tongue lolling, eyes wide, mouth gaping. Or maybe on the armour of warrior women and strong heroes who run through the myths of the Mediterranean.

But here I am, carved in the heartlands of Afghanistan and Pakistan; a mongrel, bastard child; a “Classical” character reborn outside your limits of “civilisation.”

Ayesha Purcell

Bisexual British-Pakistani from Liverpool

Ancient Egypt Galleries

The Absence of Africa

The Ancient Egypt and Sudan galleries remain the only spaces within the Ashmolean Museum with a focus on Africa. Moreover, Ancient Egypt and Sudan are partitioned from the rest of Africa and positioned to be in cultural exchange primarily with the Mediterranean world. Outside of these two Nile Valley civilizations, the collections on Africa beyond the 7th century AD are limited, and gallery space devoted to sub-Saharan Africa is non-existent.

Edil Ga’al

Student at Oxford University

The Curators’ Reply

The Ashmolean doesn’t have much material from the rest of Africa. The division of the University’s collections still reflects 19th-century ideas that separated the study of ‘great civilisations’ from other ways of life around the world. One of the legacies of these outdated and racist ways of thinking is that many sub-Saharan artefacts were added to the anthropological collections in the Pitt Rivers Museum. Our aim at the Ashmolean is to present ancient Egypt and Sudan as a bridge between Africa, Europe and Asia. While no single museum can claim to be encyclopaedic, Oxford’s collections together reveal something of the diversity of human experience across time and place.

Head of a grimacing yaksha, or nature spirit, Gallery 12, EA1994.95

Shikhandi & The Yaksha

In the Mahabharata , the Princess Shikhandini is raised as a boy, trained as a warrior and married off to the princess of another kingdom. When her assigned gender is exposed, she is cast out of court and forced to flee to the forest. Distraught, Shikhandini earns the sympathy of a yaksha, or nature spirit, who offers to switch his gender with her. The princess who entered the forest leaves as the male Shikhandi. The erasure of stories like Shikhandi’s mark a distinct shift in Indian attitudes towards queerness, from pre-colonial acceptance to contemporary stigmatization.

Kunal Patel

Antinous Tinder Profile

Natalie McGowan