ANTWERP, ARTISTIC HOME TO MANY FLEMISH MASTERS

5-minute read

By An Van Camp

Curator of the Ashmolean's major exhibition Bruegel to Rubens: Great Flemish Drawings

The majority of the drawings included in the Ashmolean's current Bruegel to Rubens exhibition (and its accompanying catalogue) were made by artists born or working in Antwerp in the 16th and 17th centuries.

In this story we will explore some sheets of these drawings by artists such as Hans Bol, Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, which are closely linked to the history, art and architecture of Antwerp.

Antwerp in the 16th and 17th centuries

The Southern Netherlands (commonly known as Flanders but roughly corresponding to modern-day Belgium) were one of the most strategically placed regions of Europe with a central position beneficial for trade and finance.

Simplified map of the Southern Netherlands in the 16th and 17th centuries

In the 16th century, the region fell under Catholic Spanish rule and was locally managed by delegated governors. Antwerp – which was perfectly situated on the river Scheldt allowing for both European and transoceanic trade – became Europe’s trading centre with huge import markets in textile, spices, gold, and silver.

A thriving art market naturally followed with the urban elite needing artworks to decorate their homes, while the many Catholic churches and monasteries commissioned major altarpieces and sculptures.

Snapshots of historical events

Against this creative and artistic backdrop, the region was in constant turmoil with the Spanish rulers not only squashing any Protestant uprisings, but also facing rebellions within their own military. Hans Bol created an expansive view of Antwerp around 1575. The seemingly peaceful city is seen from atop a hill and overlooking it many churches, monasteries, and civic buildings.

Distant View of Antwerp, Hans Bol, c.1575, pen in brown ink, with brown wash, over black chalk, on laid paper. WA1863.149 © Ashmolean Museum

While the view appears realistic, the positioning of the landmarks does in fact not correspond to their real locations. Hans Bol must have initially sketched several topographical viewpoints and ‘photoshopped’ them together to create the best view. Antwerp Cathedral dominates the skyline in the right background with the river Scheldt being barely visible in the distance. Only a few years earlier, in 1566, Antwerp churches suffered destructions during the iconoclastic riots by the Protestants.

The Iconoclastic Fury in Antwerp Cathedral on 20 August 1566, Frans Hogenberg, c.1570, etching on laid paper (from the Atlas van Stolk, Rotterdam, 50442–66). Image in public domain. Courtesy Wikimedia

Ten years later, Maerten de Vos made designs for a series of plaquettes, of which the Ashmolean holds five lead examples.

They illustrate one of the most extraordinary events in Antwerp’s history: the unpaid Spanish troops mutinied in the winter of 1576–77 and they plundered and burnt the city during what was called the Spanish Fury.

The Sack of Antwerp was particularly brutal and resulted in the tragic loss of over 8,000 citizens, as well as the destruction of the town hall. Protestants united against these atrocities and following many clashes, a peace was negotiated in August 1577, resulting in a retreat of the Spanish and Antwerp briefly becoming Protestant.

The Spanish king, however, quickly regained power in the region. Newly appointed governors made a ‘Joyous Entry’ to establish their rule. Ernst, Archduke of Austria, did so in Antwerp in 1594. The city hosted festive processions against a backdrop of monumental gateways and painted triumphal arches. Maerten de Vos made numerous sketches of allegorical and mythological scenes, which were painted all over the city.

Cadmus and Hermione: Design for the Decorations of the City of Antwerp on the Occasion of the Joyous Entry of Archduke Ernest of Austria in Antwerp, Maerten de Vos, c.1594, pen in brown ink, with brown wash, over black chalk, on laid paper. PK.OT.00058 © Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp

These decorations were often taken down after the Joyous Entry and De Vos’s drawings are therefore a unique surviving document of these ephemeral artworks.

Public survivals of Antwerp's wealth

In 1609 the Twelve Years' Truce, a major peace between the Dutch Republic (in the North) and the Spanish Netherlands, was finally reached. Around the same time Peter Paul Rubens, (Antwerp's best-known artist), started work for the local governors Albert and Isabella. Rubens had returned to Antwerp in 1608 after some years of travelling and working in Italy and Spain.

Rubens’s most famous altarpiece, The Raising of the Cross, was commissioned for the St Walburga Church in Antwerp around 1610. The church, however, was closed by the French in 1798 and subsequently demolished, after which the triptych moved to the Cathedral. The male torso, quickly sketched in charcoal with white chalk for the highlights, is a figure study for one of the soldiers supporting the body of Christ while lifting the cross.

Study of a Nude Male Torso, Peter Paul Rubens, c.1610, charcoal (wettened & partly stumped), heightened with white chalk, on laid oatmeal paper. WA1855.154 © Ashmolean Museum

Less than a decade later, around 1618, the Dominican order commissioned several artists to create an ambitious paintings cycle illustrating the 15 Mysteries of the Rosary. Barely aged 18, this was Anthony van Dyck’s first official commission, and he must have painstakingly prepared his contribution. The compositional study for The Carrying of the Cross shows ample signs of his creative process: the positions of some of the figures are still being adjusted on the paper, and in the background some heads have been ‘erased’ with white.

The Carrying of the Cross, Anthony van Dyck, c.1617–18, pen in brown ink, with brown & grey wash, over black chalk, retouched with white opaque watercolour, squared in black chalk, on laid paper. PK.OT.00123 © Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp

A few years later, Van Dyck was still working as Rubens’s most important assistant, when they both contributed to the decorations of the newly built Jesuit Church in Antwerp (now called Charles Borromeus Church). A large architectural drawing with a design for a high altar has survived.

Design for a High Altar, Anonymous South Netherlandish, c.1617–21, graphite and red chalk, brush in brown-greyish ink, with brown wash, heightened with white opaque watercolour (now oxidised), on four joined sheets of laid paper, some outlines incised for reference.On long-term loan to Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp, CVH.0084 © King Baudouin Foundation

While it does not fully match the marble altar installed in the Jesuit Church at its opening in 1621, some of its decorative elements have nevertheless been included.

Around 1628, another Antwerp artist, Jacques Jordaens received a commission to paint the four-meter-high altarpiece showing St Apollonia, the patron saint of dentists, for a side chapel devoted to her in the St Augustine’s Church. The arched drawing is particularly striking, as the martyr Apollonia suffered a particularly gruesome fate with her teeth being pulled.

The Martyrdom of Saint Apollonia, Jacques Jordaens, c.1628, brush in brown ink, with brown wash, with transparent & opaque watercolours, over black chalk, on four joined sheets of laid paper. PK.OT.00155 © Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp

The fully coloured drawing was probably created by Jordaens to show the church commissioners his final design. They must have not been entirely satisfied, because Jordaens made many alterations afterwards and he even cut out the top part of the scene to redraw it entirely. The St Augustine’s Church was deconsecrated in 1974 and the full-scale painting can now be admired in Antwerp’s newly reopened Royal Museum of Fine Arts.

More private commissions for Rubens

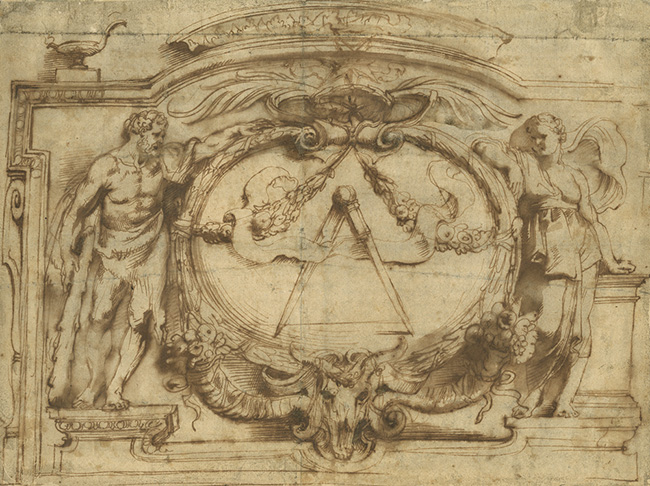

In the late 1620s, Rubens designed an elaborate emblem for the Officina Plantiniana, Antwerp’s most successful publishing house.

Design for the Printer’s Mark of the Officina Plantiniana, Peter Paul Rubens, c.1628–30, pen in brown ink, with brown wash, over traces of black chalk, on laid paper. MPM.TEK.391 © Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp

The founder’s Latin motto was 'Labore et Constantia' (Labour and Constancy), personified by the god Hercules on the right and a female figure at left. At centre, a large compass refers to the premise’s name ‘The Golden Compass’. This design was also used in the company’s publications and the decorations of the building (now the Museum Plantin-Moretus, which still houses the old printing presses, all furniture, art, and archives and is well worth a visit).

A double-sided drawing attributed to the sculptor Lucas Faydherbe shows a design for a sculpture of Our Lady of Sorrows (Mater Dolorosa) in combination with nude studies of a female model on both the front and the back of the sheet.

The sketches are done on blue paper, which allowed for black and white strokes to be drawn on a mid-tone, thus enhancing the modelling of the bodies. A marble statue matching the drawing has survived in Rubens’s funerary chapel in the St James’s Church in Antwerp. The drawing is dated just after 1640, the year Rubens died. Perhaps Rubens commissioned one his last apprentices to design a sculpture for him?

Because drawings are usually made on paper or vellum and therefore more fragile than other artworks, they are only rarely put on display. The Bruegel to Rubens exhibition is therefore a once-in-a-lifetime occasion to enjoy so many outstanding examples at the Ashmolean.

The exhibition opened on 23 March 2024 and runs until 23 June 2024.

Display in the Bruegel to Rubens exhibition. Image © Ashmolean Museum / Hannah Pye

Visit Flanders

The examples here demonstrate that Antwerp was a thriving artistic centre in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Many of the artworks and places mentioned can still be visited. Some are in churches, and others in Antwerp’s fantastic museums.

Why not enter our competition in partnership with VisitFlanders to win a trip to Antwerp?