THE FUNCTIONS OF DRAWING FROM BRUEGEL TO RUBENS

5-minute read

By An Van Camp

Curator of the Ashmolean's major exhibition Bruegel to Rubens: Great Flemish Drawings

From the practice of making copies and sketches to creating designs for other artworks, or the pure joy of self-expression and deepening friendships, drawing has a multitude of uses.

In this article, we explore these functions of drawing through a collection of exceptional South Netherlandish drawings from 16th and 17th-century Flanders, currently on show in the Ashmolean's Bruegel to Rubens exhibition. Look over the shoulder of some famous Flemish artists and glimpse beyond the studios of lesser-known draughts-people, as we gain insights into the drawings themselves.

Inside the Bruegel to Rubens exhibition © Ashmolean Museum / Hannah Pye

Introducing Flemish drawings

The group of 16th and 17th century South Netherlandish drawings we're highlighting here were from the region commonly known as Flanders. Historically this area consisted of the County of Flanders (including Bruges and Ghent) and the Duchy of Brabant (including Antwerp, Brussels and Mechelen).

The Flemish artists we've come to celebrate from this time, such as Bruegel, Rubens, Van Dyck, and Jordaens, worked and studied in this thriving region. They took inspiration from the world around them, including the cities they lived in, the people they knew, the animals they encountered, the surrounding countryside, but even further afield to the rest of Europe and, of course, Roman antiquity and the Italian Renaissance.

Different functions and materials

Broadly speaking, drawings can be divided in three major functions: making copies and sketches, creating designs for other works, or independent drawings.

The function of a drawing could naturally shift over time. Artists employed different tools depending on these functions.

Rapid sketches from life and nature were usually done in dry materials like charcoal and chalk, since they did not smudge nor did they require drying when outdoors.

Preparatory studies for paintings and prints, on the other hand, were mostly done in wet media, such as inks and washes, which allowed for fluid strokes. Independent drawings are often meticulously worked up in watercolours and even gold ink.

Copies and sketches

Aspiring artists would start their training by drawing relatively easy subjects, such as copying existing prints. By meticulously tracing the printed lines, pupils learned how to draw.

While most of these early (and often clumsy) trials were naturally discarded, a fascinating example of this practice has miraculously survived.

The young Peter Paul Rubens made copies of Hans Holbein the Younger’s small woodcuts illustrating the Dance of Death. Drawn when Rubens was only 13 years old, they already demonstrate his great talents as a draughtsman. In The Abbot and Death, Rubens clearly managed to render the figures livelier than in the original Holbein print.

The Abbot and Death, c. 1590, Peter Paul Rubens after Hans Holbein II, pen in brown ink, with brown wash, over black chalk, on laid paper © Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp

Throughout their careers, South Netherlandish artists made sketches of the world around them: the towns they lived in or travelled to, the surrounding countryside with its trees and wildlife, people they knew, and even themselves or their pets.

This lively study of a crouching and growling dog is clearly made from life. Joannes Fijt was a specialist animal artist and this is evident from the skilful way he managed to capture this rapidly moving spaniel.

Study of a Dog, c. 1630/61, Joannes Fijt, black chalk, blue transparent watercolour, brown opaque watercolour, brush in brown ink, heightened with white opaque watercolour on laid paper © Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp

Another example of a spontaneously made sketch from life is Jacques Jordaens’s study of Five Gossip Aunts, an everyday scene which he witnessed on 1 October 1659 from the window of his Antwerp studio (as he insightfully wrote on the sheet) and which prompted him to capture this scene.

'Klappeien' or Five Women Chatting, Jacques Jordaens, 1659, red chalk, pen in brown ink, with brown wash, on laid paper © Private Collection, Antwerp

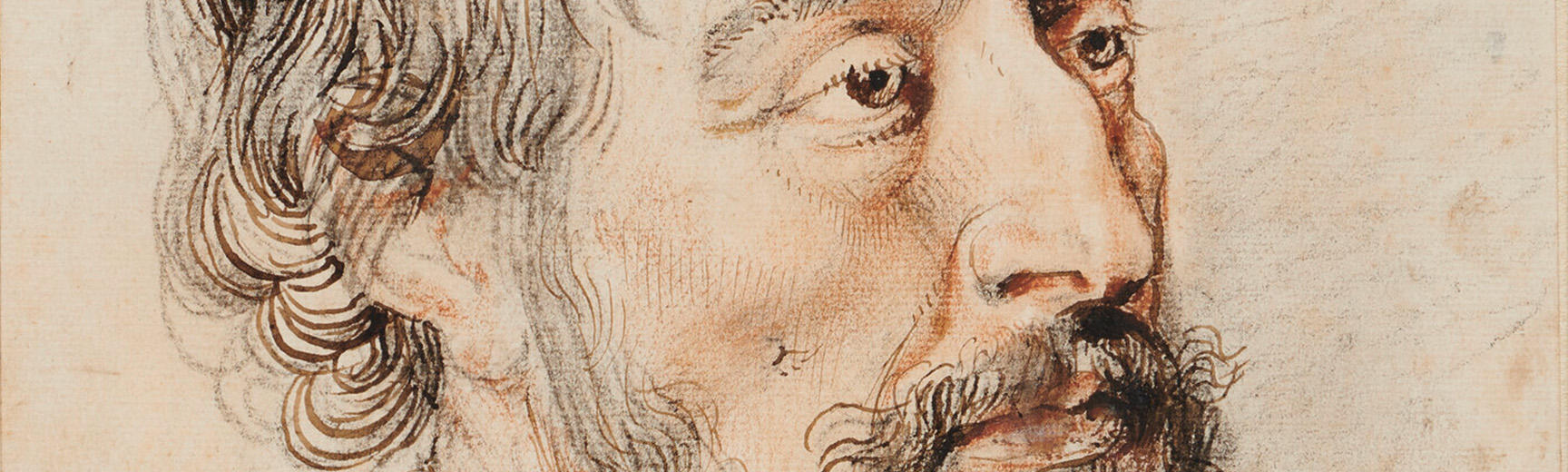

More accomplished portrait sketches from life, by the masters and lesser-known artists alike, are often what captivate us most, bringing the subjects and their characters to life.

Study of a Young Girl, Cornelis de Vos, c. 1663–5, black & red chalk on laid paper © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp

Design drawings for prints, paintings, sculpture, architecture, decorative arts, etc.

The majority of drawings which have survived from the 16th and 17th centuries were made as designs for other artworks.

These design drawings could be for paintings, prints, sculptures, tapestries, stained glass windows, silver objects, and for temporary decorations and even architectural elements. From quickly-sketched early ideas to highly worked-up presentation drawings to be shown to the commissioner for approval, these works reflect the different stages needed for the design processes.

For instance, Rubens’s Nude Male Torso served as a figure study for one of the men lifting the cross in his famous altarpiece now in Antwerp Cathedral, The Raising of the Cross. We can imagine Rubens instructing a burly dock worker in his studio to take on the exact pose which he needed for the final painting.

They were mostly made on a smaller scale than the final work (in order to save time and materials), however print and tapestry designs had to be done in the same size because they were passed to specialist craftsmen in order to transfer the design on to the final products.

One exceptional early print design is by Pieter Bruegel, The Temptation of St Anthony. The hermit is seen praying in the lower right corner, trying to ignore the demons surrounding him and attempting to distract him from his faith.

This drawing was used by a professional printmaker to copy the composition onto a copper plate to be printed (below).

The Temptation of St Anthony, Pieter van der Heyden after Pieter Bruegel I, 1556, engraving on laid paper © Ashmolean Museum

Similarly, four small roundels by the Antwerp artist Maerten de Vos served as models for metal plaquettes to commemorate the Liberation of Antwerp from the Spanish army in August 1577. The outlines in the compositions, illustrating different stages of the negotiations and the capture of the citadel, are incised with a sharp pen.

This was done in order to transfer the design on to the metal artworks. Extraordinarily, the Ashmolean also holds the corresponding plaquettes, cast in lead.

Artist Jan van der Straet spent most of his career in Florence working at the Medici court (under the name of Stradano), but continued to proudly refer to himself as Flemish, being born in Bruges. A colourful arched sheet represents an allegory of the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559, ending the 65-year-long wars between France and Spain.

The Spanish king Philip II is seen triumphant in this design for a temporary decoration to be erected on the occasion of the Joyous Entry of his governor in Italy, his cousin Joanna of Austria.

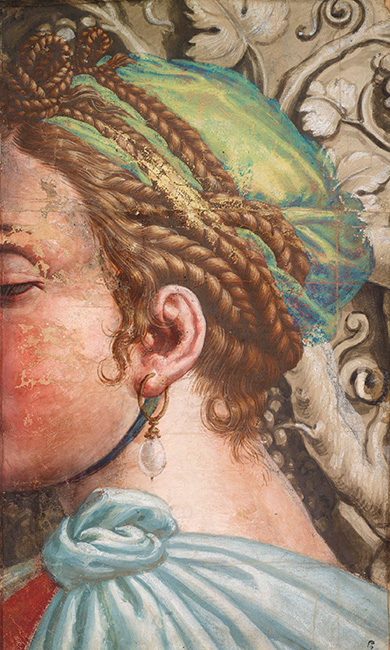

Much larger even in scale are tapestry cartoons, which were used by the weavers and therefore had to be the same size as the monumental tapestries themselves. Because of their impractical size, only fragments have nowadays survived, usually of notable details such as heads (Head of a Woman).

In the Ashmolean's exhibition, for the first time the six tapestry cartoon fragments are united (of heads, feet and even a bucket containing a dove) related to a tapestry woven in Brussels for the Vatican, The Presentation in the Temple.

The drawings for tapestries display in the Bruegel to Rubens exhibition © Ashmolean Museum / Hannah Pye

Drawing as an independent art form

A third category of drawings is not so well known. Independent drawings were not sketched or copied after something, nor were they meant as designs for other artworks. Rather, they were created as a standalone artwork in their own right.

Joris Hoefnagel specialised in cabinet miniatures, postcard-sized and meticulously drawn in transparent and opaque watercolours and even gold ink, usually on expensive vellum. Arrangement of Flowers is an exquisite example and was probably created in order to sell or present to a wealthy patron, such as the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II in Prague.

Other sheets were given or exchanged as friendship tokens, often between artists. Many of these were drawn in friendship albums, called 'album amicorum'.

These books have rarely survived, but an intact example which belonged to the historian Emanuel van Meteren, is included in the Bruegel to Rubens exhibition.

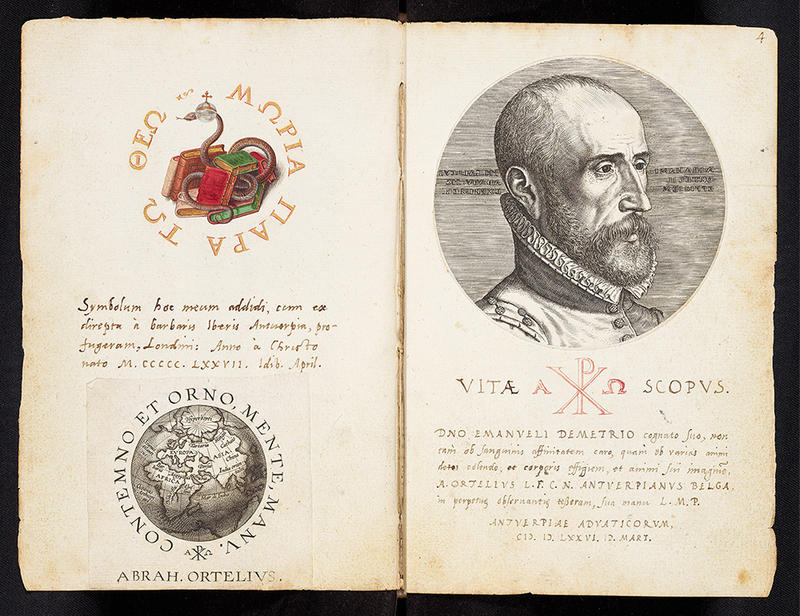

Album Amicorum of Emanuel van Meteren, 1576 & 1577, Friendship Contribution by Abraham Ortelius, folios 3v–4r, pen in brown ink, with transparent & opaque watercolours & two engravings, on laid paper © The Bodleian Libraries

Artists sometimes made landscape drawings as independent artworks as well, either for sale or purely for their own pleasure. An exquisite example is Rubens’s Woodland Scene, which he drew in his final years at his countryside estate where he escaped the hustle and bustle of his Antwerp studio.

Because drawings are usually done on paper or vellum and therefore more fragile than other artworks, they are only rarely put on display. Bruegel to Rubens is therefore a once-in-a-lifetime occasion to enjoy so many outstanding examples at the Ashmolean.

The exhibition opened on 23 March 2024 and runs until 23 June 2024.

Bruegel to Rubens exhibition walkway © Ashmolean Museum / Hannah Pye