EXPLORING MONEY THROUGH ART

5-minute read

By Shailen Bhandare

Curator of the Ashmolean's major exhibition Money Talks: Art, Society and Power

Art and money have much in common. Both influence who and what we think of as valuable. It can be surprising to think of money, so functional in form, starting its life as drawing or sculpture.

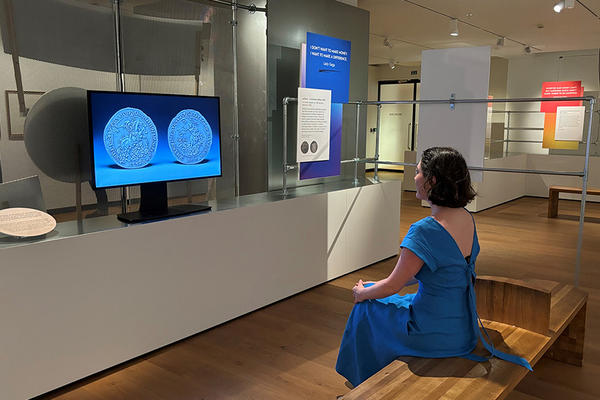

The current Money Talks exhibition at the Ashmolean explores the place of money in our world through art, highlighting a multitude of global perspectives across time. Works on show range from rare monetary portraits and historic depictions of wealth to contemporary activist Money Art, alongside more unusual examples from some of the best-known artists including Rembrandt and Warhol. Together, they expose the tension between the power of money and the playfulness of art.

Inside the Money Talks exhibition

In this article, we’ll uncover some of these perspectives, highlighting the stories that underpin the fascinating and thought-provoking themes of the exhibition.

Artists making money: ancient to modern practices

The visual aspects of money that people recognise and value are a gift to the artists who design and participate in its production, a relationship that continues to the present day. In most instances, we are unaware that we carry their artwork in our pockets.

In the ancient Greek and Chinese worlds, rare instances of artists ‘signing’ their work on money are known. During the Renaissance, a new-found interest in making medals prompted artists like Pisanello (c. 1380/1395 – c. 1450/1455) and Benvenuto Cellini (1500–1571) to engage with artistic techniques that were also involved in producing money.

Sometimes, kings expressed a special interest in the art of money struck in their names. The Chinese Song dynasty emperor Huizong (1082–1135) was a renowned calligrapher and used styles perfected by him to write inscriptions on his coins.

Bronze 10-cash piece of the Northern Song emperor, Huizong. Issued during the Daguan Era (1107) © Ashmolean Museum

Paper money has also employed artists since its introduction in China in the 10th century, and in Europe in the 17th century. To ensure the security of the notes, engravers are employed to add complex imagery, while typographers and calligraphers are commissioned to create the writing on them. Both images and lettering are purposefully designed to be difficult to imitate, and complicated abstract design forms are added to protect the notes from forgery.

Royal portraits and patterns

A wide range of creative skills and techniques left their mark on mass-produced coins and notes, from the end of the 16th century onwards. Money was inspired by artworks immortalising people and figure-heads, artistic movements and moments in time.

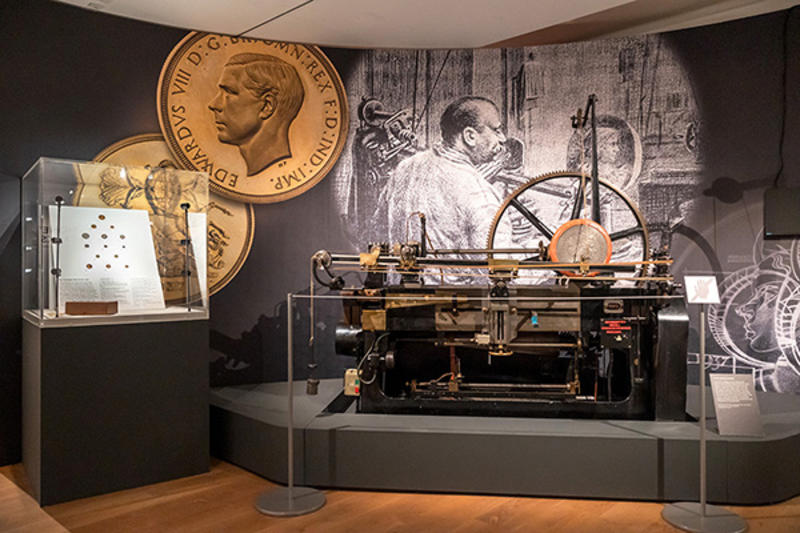

In the 19th century, advances in technology such as steam-driven machinery, changed how art was transformed into money.

The Janvier reducing machine or ‘pantograph’ enabled accurate reduction of an artwork to fit on punches and dies used to strike coins, thereby creating a mechanical bridge between creativity of the artists and functionality of the tools.

The Janvier coin reducing machine (1910) displayed in the Money Talks exhibition

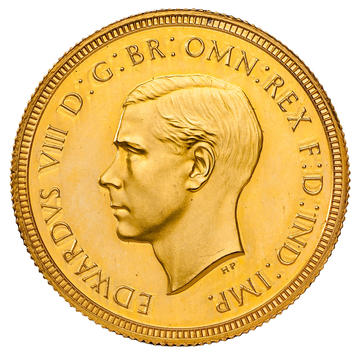

The Royal Mint has paid particular attention to recruiting artists to design its coinage. A closer look often reveals an artist’s style and personality, sometimes with hidden or surprising details. The ‘story’ of the coinage of Edward VIII, which was never issued due to his abdication, reveals how artistic engagement with coin design was a watershed moment in history.

Profile photograph of Edward VIII, Hugh Cecil, 1936 © Royal Mint Museum

Bust of Edward VIII for gold pattern for £5, £2 and sovereign, by Humphrey Paget, 1937 © Royal Mint Museum

Edward VIII wanted his coinage to be ‘modern’. This set off the artists commissioned by the Royal Mint on a quest of what ‘modernity’ means in context of money art. Edward was problematic – he insisted on breaking the convention of facing the other way than his father George V. He was also impressed by the coins of the Irish Free State, designed by Percy Metcalfe, which depicted animals in an 'Art Deco' style.

The final designs were a compromise choice between traditional heraldic designs and ‘modern’ motifs such as thrift flowers and the wren bird.

Edward VIII bronze farthing pattern with wren design, Wilson Parker, 1937 © Royal Mint Museum

Irish wolfhound design, Irish Free State coin, Percy Metcalfe, 1927 © Royal Mint Museum

Trial strikes or ‘Patterns’ were made but Edward famously abdicated in December 1936, only days before the production was to begin. The coins were never issued and as relics of an embarrassing moment in royal history, were hidden and forgotten – only to be discovered in 1970 when a Mint official retired and his office was being cleared.

It’s the first time that an entire set of these extremely rare ‘Pattern coins’ has been exhibited in an exhibition, thanks to the Royal Mint.

Iconic imagery and cultural symbolism make money an excellent vehicle to show power and wealth. This relationship is explored by artists worldwide, deploying familiar forms and devices in an ingenious manner.

The late Queen Elizabeth II is instantly recognisable across the globe through her iconic ‘monetary portraits’. Many are based on photographs of famous photographers like Yousuf Karsh and Dorothy Wilding.

Monetary portraits of Queen Elizabeth II by Yousuf Karsh and Dorothy Wilding, on show in the Money Talks exhibition

The photographic genius of these artists underwent further artistic treatment through the hands of artist-engravers when they appeared on banknotes. Celebrated artworks such as Arnold Machin’s ‘dressed head’ plaster relief and ‘Equanimity’, the lenticular (holographic) portrait by Chris Levine and Rob Munday also served as ‘monetary portraits’ of the Queen.

A version of the ‘Dressed Head’ sculpture of Queen Elizabeth II, Arnold Machin, 1966, plaster relief © The Postal Museum

Queen Elizabeth II (‘Equanimity’), C. Levine & R. Munday, 2012, lenticular print on lightbox commissioned by Jersey Heritage Trust © Jesus College Oxford, Rosaline Wong Gallery © Chris Levine & Sphere9 Ltd. Rights reserved DACS 2023

The Machin 'dressed head' bust is considered the ‘most reproduced artwork’ in the world, as it was printed over three billion times on postage stamps.

Art Nouveau banknotes

The two defining artistic movements of Art Nouveau and Art Deco left their imprint in monetary art, much as architecture, jewellery and furniture. ‘Jugendstil’ or German Art Nouveau in money can be best exemplified through the works of the Viennese ‘Avant Garde’ artists like Gustav Klimt, Franz Matsch and Koloman Moser.

Draft artwork for 50-crown note for the Austro-Hungarian Bank, Koloman Moser, 1902, gouache & coloured pencil on graph paper © Money Museum of the Austrian National Bank

These artists are now globally celebrated but in their own times, their art was severely criticised and even ‘cancelled’ in favour of more traditional designs.

The Austro-Hungarian Imperial Bank officials dismissed Klimt’s designs of banknotes as having ‘little appeal’ and being ‘one-sided’. Moser worked on several designs over more than a decade but only one ever went into final production, the one seen above that's in the exhibition with more Art Nouveau bank note print designs.

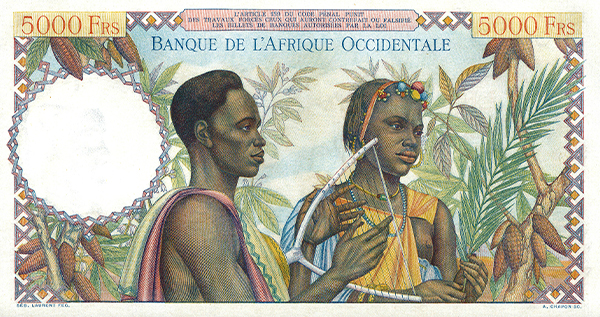

Africa's colonial currencies

Colonialism brought coins and banknotes to Africa, disrupting and reconfiguring traditional monetary systems which had deep cultural and social roots. The intervention was engineered for economic extraction and exploitation, much like the introduction of ‘modern’ forms of industry, transport and agriculture. In the Money Talks exhibition we bring in a decolonial perspective to the legacy of colonial money as a tool and a symbol of control.

Banque de l’Afrique Occidentale, 5,000-franc note, by Sébastien Laurent, 1946 © Banque de France

Banknotes designed by Sébastien Laurent, the French artist, objectify colonised West African people as ‘primitive’ and exotic. However, reclaiming the narrative power of currency, contemporary African artist Meschac Gaba highlights the ongoing economic impact of imperialism in modern African states. Gaba’s installation ‘Bank or Economy: Inflation’ (2016), in form of a market stall of banknotes, utilises money as a symbolic medium to highlight the impact of European interference in African politics and economies.

Visitors at the Bank or Economy – Inflation display in the Money Talks exhibition © Meschac Gaba, 2016 Installation, courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town, Johannesburg, and Amsterdam

Western versus Eastern perspectives of wealth

Artists have always highlighted and reflected on wealth, power and money. But the contrasting way in which money is depicted and treated in Eastern and Western traditions of art is interesting in itself.

Perhaps owing to the bad press money gets in the Bible and the Christian world view, money is often depicted in negative ways in Western Art.

Greedy usurers and tax collectors, miserly men, conniving and hoarding women are often the subjects associated with money. The ‘crookedness’ of money is also physiognomic: these subjects are often shown with grotesque features, unkempt appearances and unsavoury expressions.

Works by Masters like Rembrandt, as well as those inspired by Da Vinci and by Marinus van Reymerswale, are poignant examples. The status and power of these professionals is often ridiculed and mocked – but in Rembrandt’s case we see an exception: the tax collector was his close friend.

Portrait of Jan Uytenbogaert, ‘The Goldweigher’, Rembrandt van Rijn, 1639, © Ashmolean Museum

On the contrary, in the Eastern traditions, money is celebrated as an agent of fulfilment, plenitude and fertility.

This shift in attitude prompts Eastern artistic engagement with money to be far more positive and fun. It celebrates money’s agency in bringing prosperity, wealth and happiness. Here we see representations of gods and goddesses, symbolisms and happy cultural associations with money.

Seated figure of Kubera, the Hindu and Buddhist god of wealth, Tibet, 18th–19th century, gilt bronze © Ashmolean Museum

Money in Art: satire, provocation and value

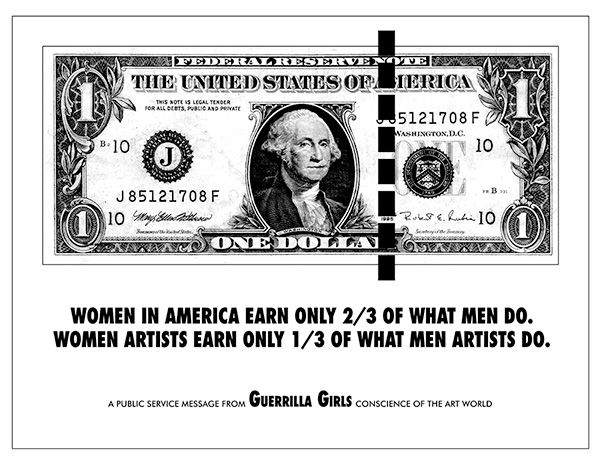

The familiarity of money makes it an excellent template to deliver artistic critiques. The artist often treads a careful line between commentary and protest, sometimes simply highlighting a tension, other times overtly promoting a cause.

Humour, satire, irony and wit are often deployed as critical tools by artists to playfully poke fun or shine a light on different social and political topics. These include many of the enduring questions and issues facing society, from the pressures of inflation to the intersections between gender, celebrity and status.

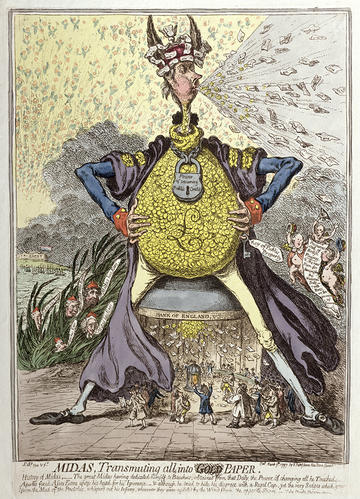

Artists from Bruegel the Younger ridiculing ‘brown-nosers’, to James Gillray lampooning a belching and farting prime minister, have included mischievous elements of visual discovery in their satirising of money.

The man with the moneybag and his flatterers, Johannes Wierix, printmaker, after Pieter Bruegel, the Younger, 1568, engraving on laid paper © Ashmolean Museum

MIDAS, Transmuting all into GOLD PAPER, James Gillray, hand-coloured etching on laid paper © New College Oxford

‘Notable Women’ – a banknote artwork by Paula Stevens-Hoare – is an intervention made at the time the Bank of England introduced new polymer £5 notes with Churchill, replacing older ones with the woman educationist Elizabeth Fry. Paula’s aim was to underscore the absence of women subjects on British currency so they over-stamped male subjects on the notes with women who fitted in with the Bank of England’s criteria of who can be depicted on a note.

The ‘Guerilla Girls’ make a succinct comment about the gender pay gap using a one-dollar bill, demarcated with a line to indicate that ‘women in America earn only 2/3 of what men do’.

Women In America Earn Only 2/3 Of What Men Do, Guerrilla Girls, 1985, Screenprint on paper, Tate © Guerilla Girls

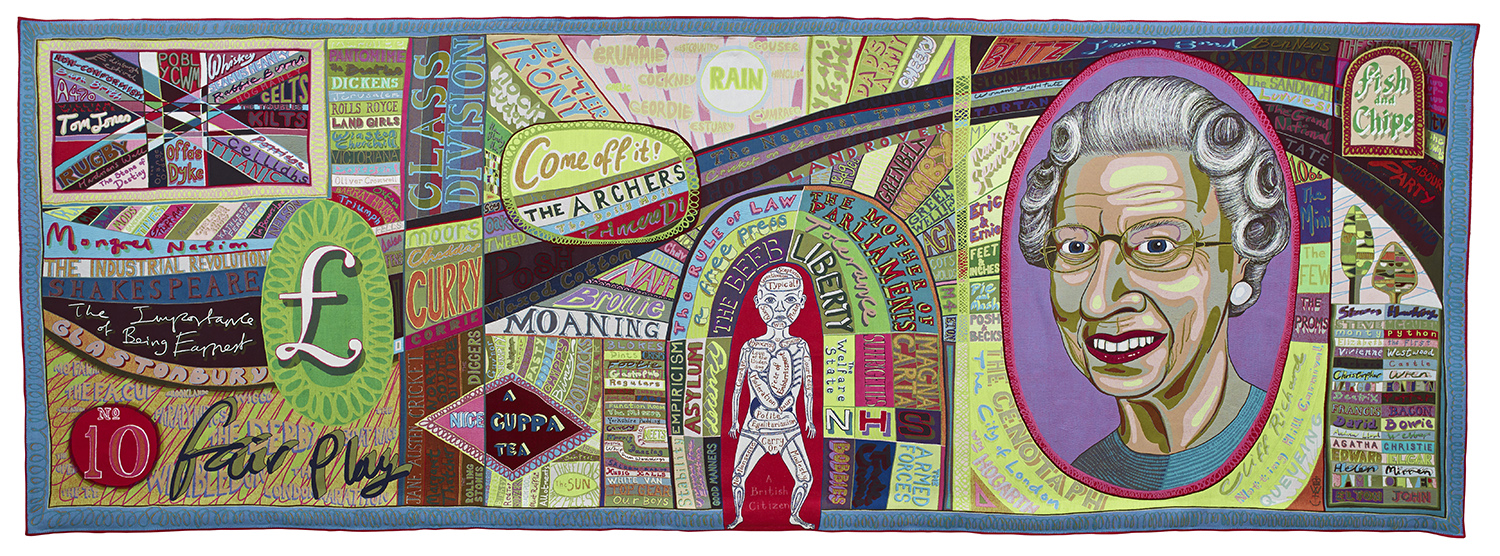

The enormous tapestry ‘Comfort Blanket’ by Sir Grayson Perry (centrepiece of the Money Talks exhibition) is based on the design of a very familiar monetary object – the £10 banknote. In Sir Grayson’s own words, it is 'portrait of Britain to wrap yourself up in, a giant banknote; things we love, and love to hate'.

Comfort Blanket, Sir Grayson Perry, 2014, tapestry (edition of 9 plus 3 APs). Courtesy the artist, Paragon | Contemporary Editions Ltd and Victoria Miro

Money is instantly recognisable. Circulated as part of our everyday lives, it is embedded in language, customs and attitudes.

As a universal symbol of capitalism, money serves as an excellent metaphor in the visual vocabulary of art. It's become a critical component in modern art. Both to comment on the narratives that give currencies their value and as a critique of capitalism itself, in a myriad of 'playful', 'provocative' and 'futuristic' ways.

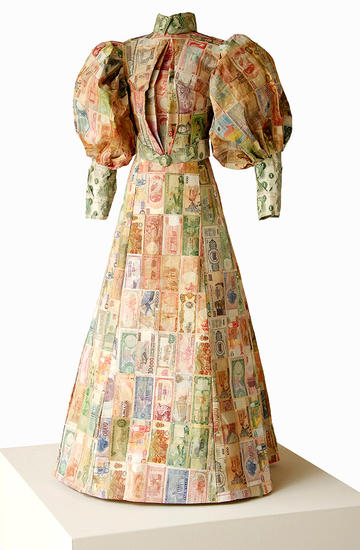

Susan Stockwell’s sculpture ‘Money Dress’ (which is also the lead image for the Money Talks exhibition) is an excellent example of a ‘feminist’ intervention using money as medium. Shaped like an impressive Victorian gown, it is dedicated to the early 20th-century explorer and anthropologist Mary Kingsley (1862-1900).

Money Dress, Susan Stockwell, 2010, International currency notes, cotton thread, canvas & mannequin frame © Susan Stockwell

‘Money Dress’ at once celebrates the global history of economically independent women like Kingsley and reminds us how many stories remain untold.

Artists also interrogate money’s powerful mediating influence on issues like war, climate change, diplomacy, and art itself.

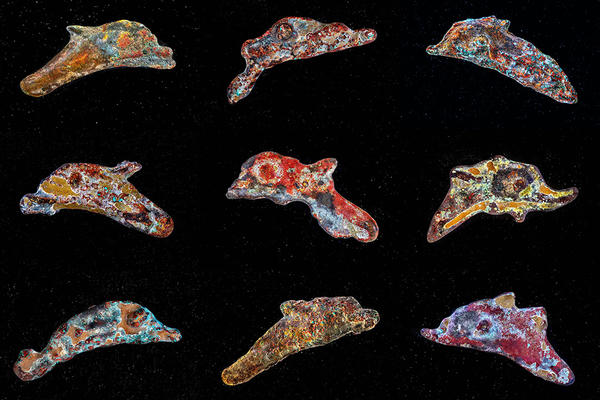

From Joseph Beuys’s ambiguous equation that ‘Art = Capital’, to Stephen Sack’s clever photographic intervention against the war in Ukraine (Black Sea Creatures), these works tap into money’s potential for artists to intervene or to pose pressing questions about money’s role in international affairs.

Joseph Beuys's Kunst = Kapital banknotes display in the Money Talks exhibition

Creatures of the Black Sea, Stephen Sack, 2023, photographs © Courtesy the artist

Stephen Sack uses poorly cast and corroded dolphin-shaped ancient coins from the Black Sea region to make a statement against the Russian invasion of Ukraine. As a result of the war, dolphins in the Black Sea have become endangered. Sack’s photographic art makes them ‘creatures of the imagination’ – from collectible monetary objects to a symbol of the ravages of an ongoing war.

Artistic protest is also now extending to the digital sphere, where new financial technologies make it possible to sell users’ private data for profit.

Digital futures and what's next for currency: NFTs, AI and cryptocurrencies

As we look to the future, the lines between art and money are blurred following the introduction of cryptocurrency, tap-to-pay and digital ‘fin tech’ financial products.

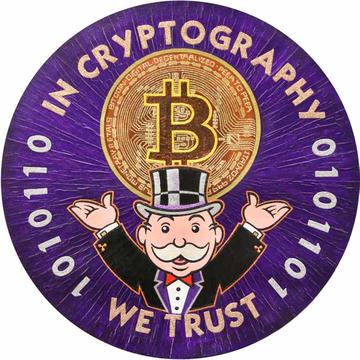

In Cryptography We Trust (based on Mr Monopoly's Milburn Pennybags), Alexander C. Cornelius, 2017, Acrylic and glitter on canvas, Haupt Collection © Alexander C. Cornelius

Artists have begun to use state-of-the-art Web3 technologies (including blockchain, NFTs and smart contracts) to encrypt and transfer digital ownership. Non-Fungible Tokens, or NFTs, are unique identifying pieces of data attached to images, which enable artists to generate, self-publish, and sell their work entirely digitally.

Against the backdrop of extensive media coverage focusing on the volatile markets for cryptocurrency and NFTs, these works envision the future of money and the reach of global financialisation.

Excitingly, an NFT based on the historic Oxford Crown coin which shows Charles I riding a horse, is the first digital artwork to be accessioned into the Ashmolean’s collection. It’s by digital artists Alex Estorick and Ana Caballero and is also on show in the exhibition.

Artifacts - Ashmolean Edition, Ana María Caballero & Alex Estorick, 2024, Single-edition generative AI. Courtesy of the artists

The artists were interested in ‘knocking the king off his horse’, replacing the static image of the king with a form of narrative coinage depicting a female figure in flux, providing an alternative story of power.

Art and money weave together a rich social, cultural and political fabric with many seams to explore. The exhibition at the Ashmolean and the accompanying catalogue mine many of them in intriguing, diverting, and enriching ways.

The objects and artworks described above are in the exhibition.

Money Talks runs until 5 January 2025.