MEDALS OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

From the Storming of the Bastille (14 July 1789) to the death of Marie Antoinette (16 October 1793)

8 minute read

By Julian Baker

Curator of Medieval and Modern Coins and Related Objects, Heberden Coin Room

The eighteenth century saw the beginnings of a considerable fashion for the production of medals, which gave a platform for the recording and dissemination of information on current events.

The French Revolution, which began in 1789, took place at a time when medallic art was evolving, and the Revolution itself fueled the developments. The dramatic and controversial events that took place in this period were interpreted from many angles.

The Ashmolean Museum holds a fine collection of medals celebrating, commemorating, and lamenting these events; the storming of the Bastille, the abolition of the French monarchy, the executions of the king and queen, and the major constitutional reforms, during the period 1789-1793. Explore a selection of medals, made in France and abroad, that represent these turning points in French history.

“The Storming of the Bastille, July 14, 1789”, by Bertrand Andrieu 1761–1822, AE cliché medal, 850mm

Made by Bertrand Andrieu, an important artist of the French Revolution, this medal enjoyed great success. For months before July 1789 there had been a stand-off between the king and the citizens of Paris. In early July there was fighting between the Parisians and King Louis XVI’s foreign mercenaries in different parts of the city, including at the Bastille, which was a prison and a depot for gunpowder. On this medal we can see the citizens in the foreground, and the Swiss mercenaries at the highest point of the fortress.

This specimen was bequeathed to Oxford University in 1834 by the Reverend Robert Finch, student of Balliol, antiquarian, and British expat in Rome of the Romantic period.

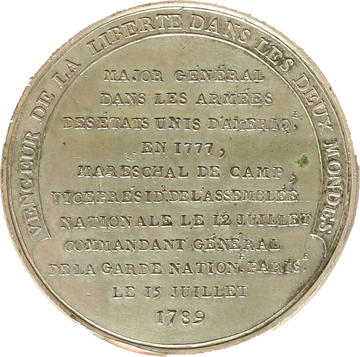

“Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette”, by Pierre-Simon-Benjamin Duvivier 1730-1819, pewter, 410mm

Marquis de Lafayette was a hero of the American Revolution and a member, since 1787, of the successive Assembly of Notables, the Estates General, and the National Assembly, which tried to steer a path through the political situation. When the crisis erupted in July 1789 he was appointed the first commander of the new National Guard. He introduced the French tricolor as its symbol. This medal was offered in 1791 to the Guard by Duvivier, engraver and medallist to the royal family.

“The Arrival of the king in Paris, 6 October, 1789”, by Bertrand Andrieu 1761–1822, AE cliché medal, 860mm

On another medal by Andrieu, King Louis XVI is depicted entering Paris. His carriage is directly beneath the statue of his father Louis XV, in the square named after him at the time. On 5 October the king had been dragged from his palace at Versailles. He was henceforth required to live in the city, in the now demolished Tuileries Palace. This medal was in the collection of the same Reverend Finch.

“Pacte fédératif”, anonymous French, gilt bronze, 24x20mm

Soon the symbolic importance of the 14 July was recognised. On this day in 1790 a “Pacte fédératif” was celebrated in a large ceremony on the Champ de Mars. Both Louis XVI and Lafayette were present. Medals such as this one were made in large numbers. They were to be worn as badges. The front symbolises the unity of king and people, with the oath itself is on the reverse.

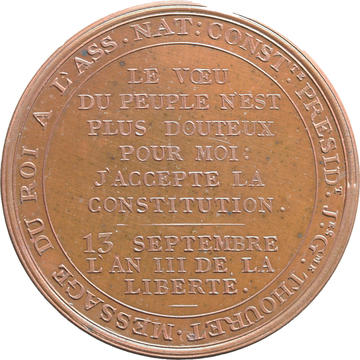

“Acceptance of the constitution by Louis XVI”, 13 September 1791, by Augustin Dupré 1748-1833, bronze, 36mm

From July 1789 the National Constituent Assembly sought to pave the way for a constitutional monarchy. The situation evolved rapidly from June 1791, when the royal family tried to flee Paris. Re-captured, the Assembly was willing to accept Louis as a constitutional monarch, although this was no longer in keeping with the mood of the population. This medal celebrates the final submission of Louis, flanked by the figures of Liberty and Justice, to the constitution. On the reverse we read his message to the Assembly: “I am no longer in doubt about the will of the people”. The medallist Dupré, a pupil of Jean-Louis David, had succeeded Duvivier in April 1791 as the main engraver to the French state.

“Celebration of the republic”, 1792, anonymous French, bronze, 23mm

The continued unpopularity of the royal family, now back in Tuileries Palace, and the threat of interventions from abroad led to the imprisonment of the king and queen in August 1792. A republic was proclaimed on 21 September. This popular medal celebrates this. The front combines the ancient symbols of the Republication Roman fasces and the Phrygian cap.

“Louis XVI parting”, 21 January 1793, by Conrad Heinric Küchler 1740-1810, bronze, 47mm

From this moment onwards, the fate of the royal family gripped people’s attention in monarchist Europe. On the reverse of this medal Louis takes leave from his wife Marie Antoinette and their children. The pose and sentiment are quite modern for the age. Küchler was the engraver at Matthew Boulton’s Soho mint in Birmingham. This and the next medal were donated to Oxford University by Matthew Boulton the Younger.

“Execution of Louis XVI”, 21 January 1793, by Conrad Heinrich Küchler 1740-1810, bronze, 50mm

This companion piece to the previous one shows us approximately the same view as #3. The square had in the meantime been renamed Place de la Liberté after a statue of liberty which replaced that of Louis XV. The current name Place de la Concorde was chosen after the reign of Terror. We witness here the moment the king’s head has come off and is shown to the members of the National Guard and other spectators.

“Lamenting the death of Louis XVI”, 21 January 1793, by Daniel Friedrich Loos 1735-1819, Silver, 30mm

A fine series of silver medals was produced at the royal Prussian mint at Berlin at the time, engraved by Loos. They are directly accusatory. The mourning figure of royalist France, wearing a cloak embroidered with fleurs-de-lis, is holding the king’s urn. The inscription reads “cry for and avenge him”. A set of the Loos series of medals was bequeathed to the Ashmolean Museum from the estate of the famous geologist Walter Calverley Trevelyan.

“Execution of Marie Antoinette”, 16 October 1793, by Conrad Heinrich Küchler 1740-1810, bronze, 48mm

Marie Antoinette was to follow her husband to the same guillotine half a year later. Küchler’s design is reminiscent of the sketch by Jean-Louis David which shows the queen on her way to the execution, hands tied behind her back and in simple garment and cap.

“Execution of Marie Antoinette”, 16 October 1793, by William Mossop 1751-1806, white metal, 33mm

The designs of Loos inspired, in spirit and appearance, the Irish medallist Mossop to conceive a similar series, in a baser metal, at Dublin. The reverse proclaims that Marie Antoinette was “sacrificed by the dissidents. Cry for and avenge her”.

“Louis (Charles) and Marie Thérèse”, 1794, by Daniel Friedrich Loos 1735-1819, Silver, 30mm

Two children survived the deaths of Louis and Marie Antoinette. “QUAND SERA-ELLE LEVEE”, underneath the curtain, relates to their fate: when will it be revealed? In 1795 the Dauphin Louis (XVII) died at the age of 10, and in the same year his older sister was allowed to escape to Austria.