RAPHAEL AND THE ART OF EMOTION

"Raphael was born in Urbino … to Giovanni Santi, a painter of no great excellence and yet a man of good intelligence…who directed him from birth to the art of painting. Giovanni insisted that Raphael should not be fed by a wet-nurse, but rather that his mother should continuously suckle him…."

With these words, the writer Giorgio Vasari evoked the beginnings of the life of Raphael Sanzio (or Santi) in The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550 and 1568). The affection throughout the artist’s childhood, which Vasari described, must have shaped Raphael’s temperament. He had a gracious and affable personality, which resonates in much of his art, and which gained him the patronage of popes and the friendship of humanists and leading artists.

Raphael was born at Easter time of 1483, on 6 April, according to some early sources. His premature death, aged only 37, did not preclude him from becoming one of the most influential artists and greatest storytellers of Western Art. At the heart of this success laid a supreme technical virtuosity and versatility, paired with an unrivalled visual culture.

Raphael and Drawing

Raphael’s creativity was driven by the process of drawing. Whether tentatively sketching, or moving with inspired conviction, his hand generated lines that gave shape to his pursuit of eloquent forms. By following his hand on the paper, we can witness the artist’s ideas emerging.

Raphael used drawing as a means of observation, as a mode of experimentation, and as a way of reflecting on human emotions and actions. All this is evident in a theme recurrent in his career, that of the Mother and Child. Raphael explored this universal subject, thinking (through drawing) of ways to articulate physical intimacy, and how to convey vitality, weight and character.

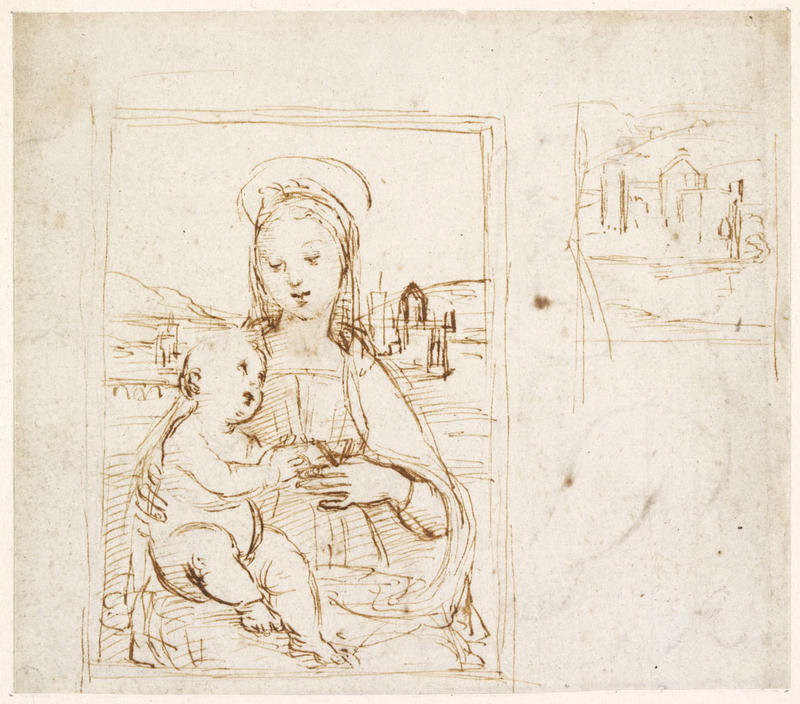

1. Raphael, Studies for the Virgin and Child with a book, c.1503 Pen and brown ink over blind stylus, WA1846.152a

The Ashmolean Museum is home to an outstanding group of Raphael’s drawings – the most significant for art historical significance and quality in the world. This collection alone illustrates Raphael’s ceaseless variations on the theme, increasingly sophisticated graphic intelligence, as well as an ability to exploit all the drawing media and techniques available to him.

In an early sheet of c. 1503 (1), a preparatory study for a painting now in California, Pasadena, Raphael pushed traditional boundaries by fusing his knowledge of the earlier treatments of the theme in sculpture, painting and drawing, with observations from life. After experimenting freely with the blind-stylus, a tool which leaves near-invisible indentations on the paper, Raphael turned to the indelible pen and ink to shape an enduring image. With only a few strokes of the tool, he experimented with possibilities for a landscape setting and refined his thoughts on the formal and psychological relationship of the two figures. He revised the position of the child’s head, now tilted to meet that of his mother, a small but dramatic modification that charged the composition with human sympathy.

2. Raphael, Studies for the Virgin of the Meadow, c. 1505 Brush and wash over leadpoint and over a faint grid in leadpoint, WA1846.161

The skill with which Raphael was able to express form effectively, with so little, remains a constant feature of his drawn output. In thinking of a painted group of the Virgin and Child (2), now accompanied by the young St John Baptist (The Virgin of the Meadow, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum), Raphael used his painterly brush, deepened in radiant brown-orange wash. He used only a few touches of white lead on the child’s face, but otherwise exploited the white of the paper, to suggest the fall of light for a luminous effect. Always stimulated by contrasts, Raphael turned to red chalk to make a linear sketch of a mother protectively grasping her baby at the top left.

3. Raphael, A seated mother embracing her child, c.1512 Metalpoint with white heightening on grey prepared paper, WA1846.202

The theme of the mother and child takes an earthly and secular tone in a small scale sheet (3), perhaps conceived as an independent drawing to be donated as a token of friendship, or to be kept as a model in the workshop (the design does reappear in a later print and as an underdrawing in a school painting). The artist captured a moment of extreme tenderness and intimacy of everyday life. The use of the laborious and unforgiving technique of metalpoint, which was gradually abandoned by other artists, testifies to his talented hand and fondness of drawing.

4. Raphael, Studies of a kneeling woman, c. 1512 Black chalk, WA1846.198

Another sheet drawn around the same time (4) illustrates the artist’s ability to adapt the various techniques to his purpose, as well as a range of expressive modes. Raphael intended this kneeling woman, caught in an animated twisting pose, to direct the viewer’s gaze across the large-scale fresco of the Expulsion of Heliodorus, where female protectiveness would contrast with violent aggression. Chalk in hand, Raphael conveyed the shape of her masculine neck and the weight of her drapery folds around the shoulder. She is tightly grasping her restless boy, who naturally attempts to escape. Here, Raphael used swift, linear marks with the medium, yet these suffice to convey the urgency of the moment.

Art that Endures

Often seen as a remote artist, embodying classical and idealised concerns which may seem obsolete today, these drawings are a powerful reminder of why we should celebrate Raphael 537 years on. It is art to cherish for its simplicity and beauty, but above all, it is imbued with human emotions, which surpasses the limits of time.

WATCH

https://www.youtube.com/embed/nNgGpyRHuBU?controls=0

Dr Catherine Whistler, Keeper of Western Art, on the great and unrivalled collection of Raphael drawings at the Ashmolean Museum.