SHOUT OUT FOR WOMEN

March is Women's History Month – an international month-long celebration of women's contributions to history, culture and society, with International Women's Day falling on 8 March.

Join us in sharing the Ashmolean's collections and stories which celebrate women’s achievements in art and archaeology throughout history and today. (Header image: The Tragic Muse, detail, by Angelica Kauffman.)

ARTWORKS BY WOMEN & CELEBRATING WOMEN IN OUR COLLECTION

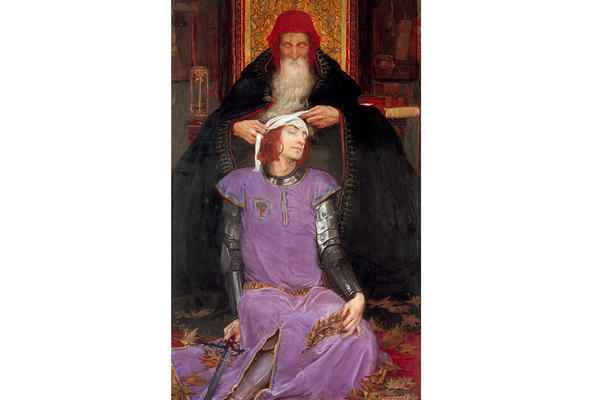

Time the Physician by Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale, 1900

Cretan Snake Goddesses

Portrait of Elizabeth Siddal, by Rossetti, pen & brown & black ink, 1855

A 'Forest Floor' Still life of Flowers by Rachel Ruysch, 1687

Talisman II by Barbara Hepworth, 1960

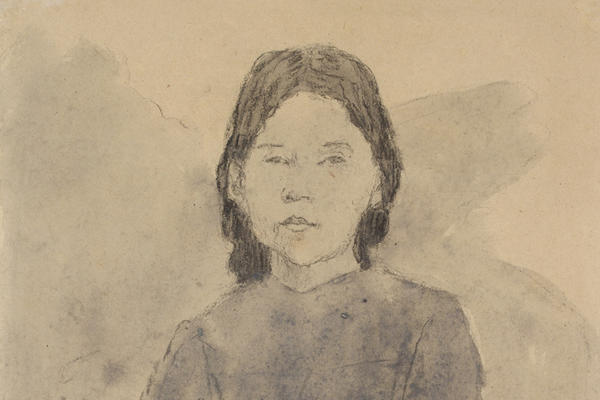

Gwen John: Seated Girl

Queen Agathocleia Indo-Greek sliver drachm, front and back, 180 BCE to AD 10

Copy of a wall painting from Queen Nefertari's tomb by Nina de Garis Davies

Acquisitions by Curator Mary Tregear

Cloister Lilies by Marie Spartali Stillman

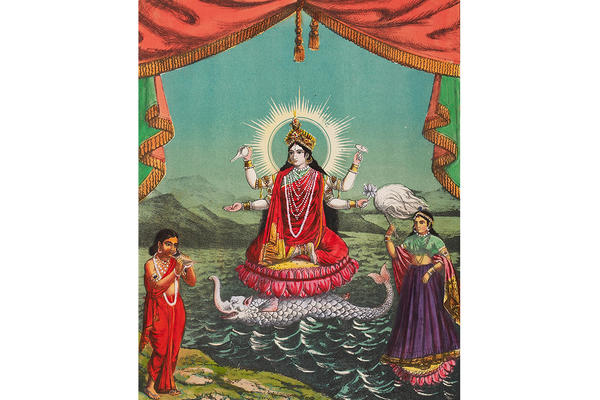

Ganga Devi print, late 19th century

Elizabeth Sonrel: Les Rameaux

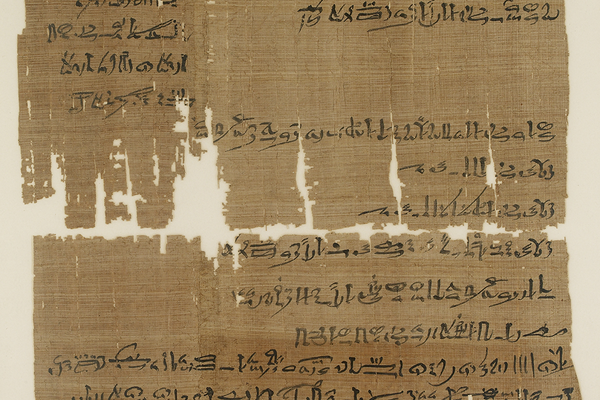

Ceremonial Flint Knife discovered by Annie Abernethie Quibell

WOMEN'S STORIES

Ariadne, an unsung ancient Greek heroine...

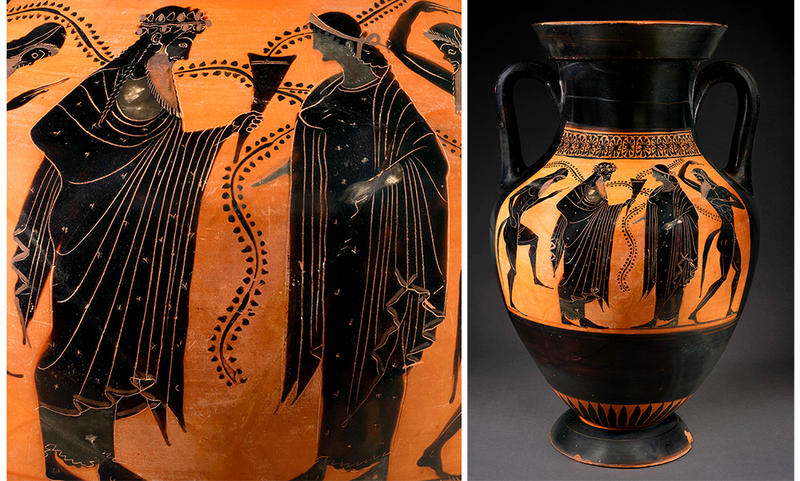

Left detail and right Attic black-figure vase depicting Dionysus and Ariadne attributed to the Rycroft Painter, 530–520 BCE, ceramic, h. 47 cm © Ashmolean Museum

In Greek myth, the Cretan princess Ariadne is an unfortunate figure, although perhaps an unsung heroine.

Firstly, she betrays her family in order to help the hero Theseus kill her half-brother, Asterion the Minotaur, who's hiding in the depths of the Labyrinth.

In most versions of the myth, Ariadne gives Theseus a ball of thread, often said to be red, to help him retrace his steps and escape the Labyrinth.

Then, her reward is to be betrayed in turn, when Theseus abandons her on the island of Naxos. Her fortunes, however, improve when the wine-god Dionysus finds her and they fall in love.

The vase (above) was painted around 530–520 BCE and shows Ariadne as the consort of Dionysus. She is very rarely shown with Theseus in Greek depictions. Vase painters tended to repeat the same scenes: Theseus kills the Minotaur and Ariadne drinks wine with Dionysus.

Although there are no recognisable depictions of Ariadne from this period, there are a number of colourful frescoes showing women in elaborately woven and embroidered clothing.

...and the women of Crete

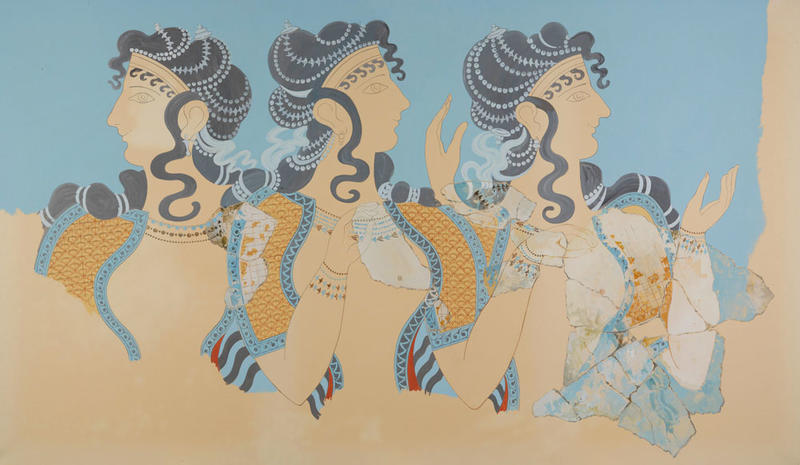

Restored watercolour 'Ladies in Blue' Fresco, undated by Émile Gilliéron père (1850–1924), watercolour, 95 × 161 cm © Ashmolean Museum

Textile manufacture was the most important export industry in Bronze Age Knossos, and depictions such as the ‘Ladies in Blue’ Fresco shows that women remained closely associated with these colourfully dyed textiles and perhaps controlled their production. Ariadne’s ball of thread could be a distant memory of the role of women in the Bronze Age rather than just a symbol of betrayal.

Attic vase

AN1911.256

Ladies in Blue Fresco

AJE/4/1/12/1/3

Not on display

Clara Peeters, Still Life of Fruit and Flowers, 1612–1613

Still Life Painting of Fruit and Flowers by Clara Peeters, 1612-1613 © Ashmolean Museum

Although little is known about her life, Clara Peeters is thought to have been one of the first professional women artists of the Dutch Golden Age and early modern Europe.

This elaborate still-life, at 64cm wide x 89cm high, is one of her largest paintings and shows a table richly laden with fruit, flowers, nuts and shrimp. It’s executed in oil on copper. Copper was a popular choice for artists at the time because it lends itself particularly well to finely detailed brushwork and is a non-absorbent surface.

The coins you see on the right of the painting helped to date the work to after 1609, while the silver wedding knife appears in five of her other paintings.

It's a highly skilful work and is part of one of the most comprehensive collections of 17th-century Dutch and Flemish still-life paintings in the world. The collection was put together by Theodore Ward and his wife Daisy Linda Ward (1883–1937), a painter from New Jersey, who bequeathed the collection to the Ashmolean.

WA1940.2.61

On display in the Still-Life Paintings gallery 48

Angelica Kauffman, the female gaze, 1770s

Left: Portrait of Angelica Kauffman, Francesco Bartolozzi after Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1780. Right: The Tragic Muse (black chalk), Angelica Kauffman, 1770–1782 © Ashmolean Museum

Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807) was a star of the art world in the 18th century. The Swiss-born painter was prodigiously talented, having been trained by her artist father in Italy. She moved to London in 1766 and became a founding member of the Royal Academy in 1768, one of only two women members with Mary Moser (1774–1819).

In London she established a reputation as one of the outstanding contemporary painters in Europe, and became an ally with Sir Joshua Reynolds in the advocacy of history painting and the 'Grand Style'. Her home in Golden Square in Soho was a celebrated meeting place for artists, musicians and wealthy sitters.

Kauffman's paintings emphasised the female experience, which was radical for the time. Her work is currently featuring in a major exhibition at the Royal Academy.

WAHP43641 & WA1955.15

View on request in the Western Art Print Room

Julia Margaret Cameron's intimate photographs, 1867 & 1869

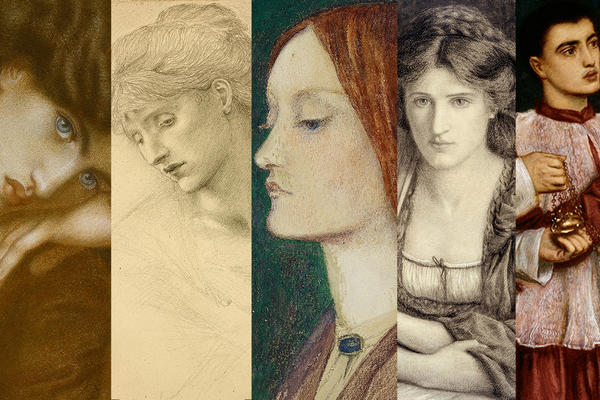

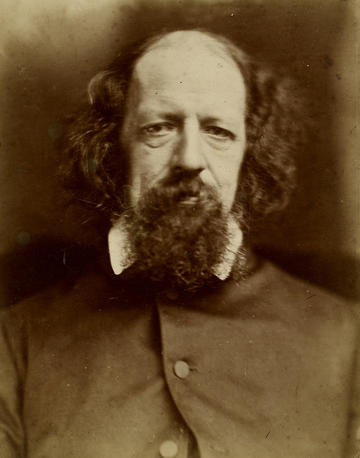

Left to right: 'My Favourite Picture of all My Works' (Julia Jackson); Sir Alfred Tennyson; Mary Pinnock as Ophelia; all 1867. Far right: My Ewen's Bride ('Annie Chinery') 1869. By Julia Margaret Cameron © Ashmolean Museum

Julia Margaret Cameron was an early pioneer of British photography and well known for her soft-focused portraits. She was greatly admired by the Pre-Raphaelites.

Her photographs were rule-breaking: purposely out of focus, and often including scratches and smudges. She also posed her sitters as characters from biblical, historical or allegorical stories.

Cameron was born in Calcutta in 1815. But she only started taking photographs in her 40s, after moving to England in 1845. She made her home in Freshwater on the Isle of Wight.

Early in 1866, Cameron moved into a highly creative period with the camera. She started to take a new direction as her children had all left home, moving closer in to the subject.

Her photographic career, however, was very short. She only worked for 11 years, but she created over 1,000 photographs of many famous people and family friends.

Lena Fritsch, the Ashmolean's Modern and Contemporary Art Curator, reflects:

'She creates these really dreamy images and the soft focus photographs of women link to her concept of beauty which is a very Victorian, English concept of beauty, at the time. A Christian concept, also inspired by classic mythology.

'And the sitters are interesting. She has all these different people in front of her lens. Photographs of Julia Jackson (above left) are in the Ashmolean collection, who was Virginia Woolf's mother. Very beautiful photographs of her.

‘But then all these different important men. John Herschel; the dramatist Henry Taylor; Charles Darwin was photographed by her.'

WA.OA1348 & WA.OA1352

Not on display

Julia Margaret Cameron & her contemporaries

View on request in the Western Art Print Room

Sarah Acland, Victorian artist and pioneer in colour photography

A Study of a Fish, Sarah Acland, 1877 © Ashmolean Museum

Sarah Acland's father was a good friend of writer and art critic, John Ruskin. In the 1860s, Ruskin became her drawing tutor and imparted his beliefs on the power of colour to unlock the secret beauty of nature.

Acland's earlier work, including this vibrantly coloured Study of a Fish in the Ashmolean's collection, is full of Ruskinian 'truth to nature' naturalism. But Acland also carried Ruskin's lessons on colour forward as she forged a career in photography.

In 1894, she joined the new Oxford Camera Club as its first female member, later becoming vice-president. Her most important contribution to the field of photography was her work using the Sanger Shepherd method, which had been invented just before 1900.

Autochrome photograph of Sarah Angelina Acland, with her Portuguese guitar & her dog Chum, Oxford, August 1910? © History of Science Museum Inv. No. 17853

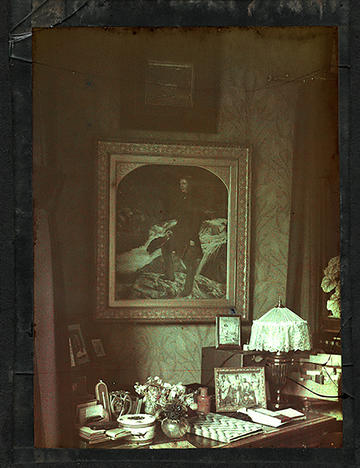

Sarah Acland, Colour Photograph (Autochrome) of the Millais Portrait of John Ruskin, hanging in Sarah Acland’s House at Park Town, Oxford, 1913–17 © History of Science Museum

Acland also paid tribute to her great teacher using another early colour photography technology, the autochrome. She owned Millais’s celebrated portrait of Ruskin and photographed it in her study at 40–41 Broad Street in the mid-1910s (above right). Using all of the colour technology at her disposal, she tried to capture the portrait’s colours as accurately as possible, in accordance with Ruskin’s truth to nature beliefs.

A blue plaque was installed in 2016 at 10 Park Town, Oxford, where Acland lived, to recognise her pivotal role as a ‘pioneer of colour photography’.

Read more about Sarah Acland and other Victorian women pioneers in colour technology here

Study of a Fish

WA.RS.UF.44.a

View on request in the Western Art Print Room

Fang Zhaoling, Lotus, 1980

Lotus by Fang Zhaoling, 1980

This striking hanging scroll created in ink and colour on paper is by Fang Zhaoling (1914-–2006), one of the foremost women artists of 20th-century China. Born in Wuxi in Jiangsu province, she was educated privately at home and later attended school in Shanghai and university in the UK, at Manchester.

She led a remarkable life. She married in 1938 and after several difficult years in war-torn China, she and her husband settled in Hong Kong. Following his early death in 1950, Fang Zhaoling resumed the painting studies of her youth and counted among her teachers leading artists such as Zhao Shao'ang and Zhang Daqian.

In the 1950s she studied at Oxford and she spent much of the following decade in London.

She experimented with abstract styles, but always remained true to the traditions of Chinese ink paintings, which she often made contemporary through her choices of humanitarian and environmental subjects.

Throughout her career she exhibited widely in the United Sates, Europe and East Asia. She travelled extensively. In 1973, she returned to China to climb Mount Huang in Anhui province.

LI2153.4

Not on display

Buy the print

Elvira Bach, Untitled, 1983

The German artist Elvira Bach (b. 1951) is best known for her stylised and flamboyant self-portraits, in which she portrays herself as a spiky character with red lipstick, lacquered nails, and high heels. In the 1970s and 80s, she focused on scenes from her world of artists, parties, and romances in West Berlin.

Her gouaches and pastels show a female figure lying lovesick on a bed, dancing in San Domingo, or catching a torrent of spilled red wine.

In this gouache drawing, Bach's avatar lies admiring herself in front of an array of accessories, mirrors, and pocket change, with the reflected silhouette of a male onlooker in the foreground.

Bach’s work captures both the dynamic energy of West Berlin, as well as the growing impact of the feminist New Women’s Movement in Germany, who marched under the slogan ‘The private is political’.

Bach came to Berlin in the early 1970s to study at the Akademie der Künste, where she befriended other young students like Salomé and Rainer Fetting. Together with other Berlin artists, including Luciano Castelli and Ina Barfuss, they became known as the ‘Junge Wilde’ or ‘Young Wild Ones’. They quickly gained international acclaim for their exuberant figurative artwork that drew on Germany’s Expressionist tradition of gestural painting.

Like Bach, many of these artists dealt with personal themes of gender and sexuality in their work. In a subversion of male artists’ objectification of the female subject as a muse on a pedestal, Bach’s sensitive and reflexive self-portraits celebrate herself as a complex figure with deep interiority, flaws and all.

Her work featured prominently in our Young & Wild? Art in 1980s Germany: Punk, Painting & Prints exhibition in 2022.

WA2002.197.1

Not on display