PRE-RAPHAELITE STUNNERS AND THEIR STORIES

Who were the 'stunners'?

6-minute read

The Pre-Raphaelite artists were inspired by all sorts of things, from medieval ballads about star-crossed lovers to the simple beauty of a flower. The world seen through their eyes was full of stories and full of wonders.

But, they are perhaps most famous for their pictures of beautiful women whom Dante Gabriel Rossetti called 'stunners'.

Some of these women became Pre-Raphaelite painters' wives and lovers, and were often idealised as extremely beautiful figures with supernatural energies. Some chose their own styles, clothing and accessories, and became fashion icons of their day.

As models they often wore floating, unstructured dresses, disposing of the corsets and crinolines of Victorian convention. They cultivated their own images, and their portraits show conscious participation in the development of Pre-Raphaelite visual culture. Some of them were also artists and designers in their own right.

Below we look at four of these ‘stunners’ – and the work of a male artist who produced images of male ‘stunners’ – while exploring their artistic achievements and stories.

Elizabeth Siddal (1829–1862)

Elizabeth Siddal was the only female artist to exhibit alongside the Pre-Raphaelites, at the summer exhibition at Russell Place in 1857. She was the wife and muse of the group’s leader, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and was one of the most famous Pre-Raphaelite ‘stunners’, painted extensively by the Brotherhood. She became one of the famous faces of the Victorian age.

But Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal was far from a passive ‘stunner’. She was an artist herself, and remarkable as a working-class woman, for her time, in her intention to become a professional painter. She shared a Pre-Raphaelite passion for literature, writing her own poetry and choosing literary subjects for her pictures.

Lizzie entered the Pre-Raphaelite circle in 1849 or 1850, having been spotted by Walter Deverell while working in a hat shop in Leicester Square in London. She initially modelled for a number of Pre-Raphaelite artists, including Holman Hunt and Millais, but from 1851 she modelled exclusively for Rossetti and began to take art lessons from him. Rossetti encouraged ‘Lizzie’ in her own artwork and poetry.

Although her striking copper-coloured hair didn’t conform to early Victorian notions of beauty, her wistful quality as a model was often observed.

Rossetti’s drawings of Lizzie were frequently made in the evening, under conditions of candle or gaslight. The drawing above, by Rossetti, is unusual in showing her full face, and the dramatic contrasts of light and shade hint at her changing moods, with an underlying theme of melancholy introspection.

From the intense closeness evident in the drawings and watercolours by Rossetti, the couple moved to a period of estrangement and then, in 1860, to marriage, but sadly, Siddal died of an overdose in 1862 after giving birth to a stillborn child. She had become addicted to laudanum which she took for frequent bouts of ill health.

One of Siddal’s most successful drawings is the illustration to Robert Browning’s poem, ‘Pippa Passes’ (below left). It was shown to John Ruskin in 1855, who offered her a quarterly allowance of £150 per annum in exchange for all that she produced.

Browning’s poem, set on a spring day in 14th-century Asolo in Italy, describes young Pippa’s experiences of the town. In his ode, prostitutes call to Pippa from the steps of a church, which Siddal has changed to a park surrounded by railings. Her picture challenges Pre-Raphaelite art convention in its suggestion that a woman can take advantage of the freedom the city offers without being compromised or corrupted.

Lizzie knew the difficulties of charting her own path in London and had to break through many Victorian stereotypes and social rules.

In another enigmatic drawing, Two Lovers Listening to Music (above right) bought from Siddal by John Ruskin in 1855, the landscape evokes the countryside around Hastings, where Siddal and Rossetti spent a summer holiday in 1854. It was to Hastings, too, that they went to get married in 1860. The subjects, however, are unidentified.

Lizzie Siddal produced over 100 works of art in her short life. She’s buried in Highgate Cemetery, London, in the Rossetti family plot.

Jane Morris née Burden (1839–1914)

Jane Morris was an exceptional woman, who, despite having little childhood education became hugely accomplished, speaking French and Italian and herself a talented embroider who played an important role in Morris & Co and the Art and Crafts movesment. Outside her immediate group of fellow Pre-Raphaelites she moved in the upper circles of poets, politicians and aristocrats.

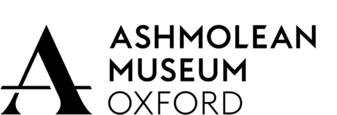

She modelled countless times for the Pre-Raphaelites especially for Rossetti after Lizzie Siddal’s death. He became obsessed with her and she posed in many different literary characters and everyday setting. Rossetti particularly used Jane Morris as the model for many of his large-scale drawings and paintings, in representations of mythological characters.

These paintings and drawings including the one above of ‘Reverie’ often have a meditative or melancholy tone. It’s difficult to avoid associating this with Jane’s marital situation and the complications caused by her relationship with Rossetti. This drawing, which the artist bequeathed to Jane, is a replica of another chalk drawing that belonged to Rossetti’s close friend Theodore Watts-Dunton. The pose is loosely based on one of the photographs of Jane taken in Rossetti’s garden in July 1865.

Jane had become involved in the 1850s with the Pre-Raphaelites in Oxford, where she lived and was spotted by them. She modelled as Queen Guinevere in Rossetti’s murals in the Oxford Union in 1857 and subsequently married William Morris in 1859. William was besotted with her, but their marriage wasn’t easy.

She had an affair with Dante Gabriel Rossetti, which lasted over a decade. The three had a complicated arrangement and they even took a shared lease of Kelmscott Manor, where they spent holidays together.

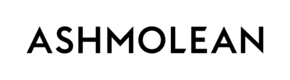

By the late 1860s Jane and Rossetti had become intimately involved, and her striking looks are a familiar feature in his later work. Jane suffered from recurrent bouts of ill health and was often unable to sit up because of backache or dizziness. It was after one such bout that Rossetti captures her relaxing reading a newspaper on the sofa. This was in 1870, when they were both staying at a cottage owned by the artist Barbara Bodichon at Scalands in Sussex.

Janey was individual and influential in her style opting for medieval dress at her home at Red House in London, and dozens of ‘strings of outlandish beads’ instead of the corsets and crinolines of the age.

It was the process of decorating Red House, the Morris’s new home which led to the birth of Morris and Co. Jane was actively involved in the production of the company from the beginning, working as an embroider for the company and went on to manage the embroidery department, passing this role and skill on to her daughter May. Jane died in 1914 outliving both Morris and Rossetti.

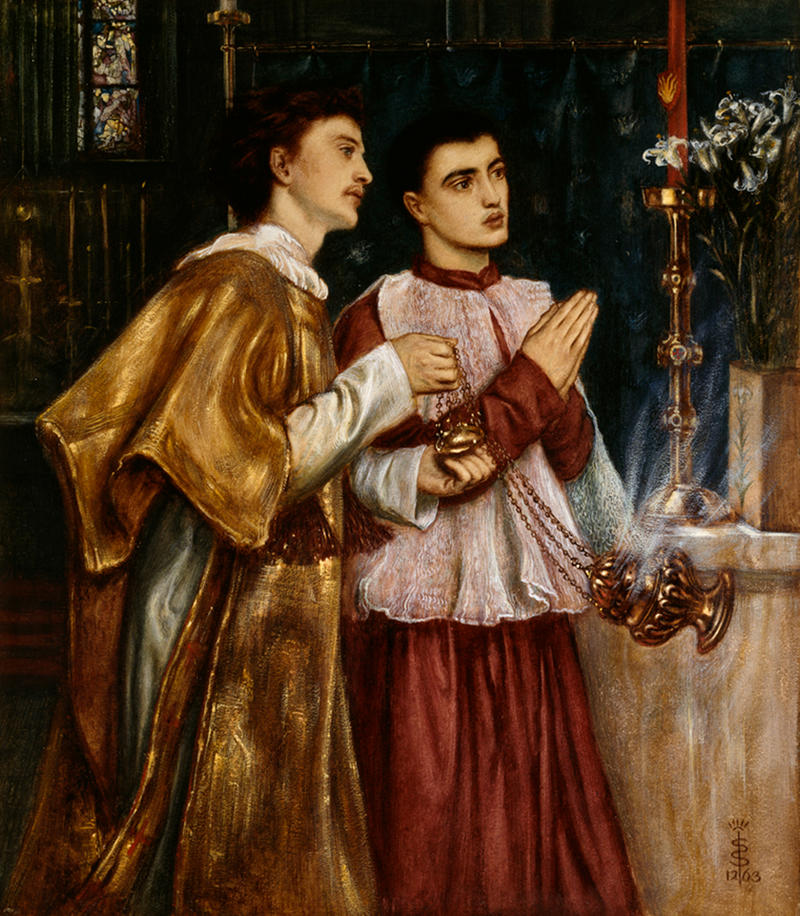

Simeon Solomon (1840–1905)

The Pre-Raphaelites talked about 'stunners', and they usually meant beautiful women. But in the work of Simeon Solomon, one of the younger artists drawn into the Pre-Raphaelite circle, we see a homoerotic counterpart to the female stunners of Rossetti.

Simeon Solomon was the youngest in a Jewish family of talented artists. He studied at the Royal Academy Schools and met members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle in 1857, first exhibiting his work at the Academy in 1858. Solomon lived in London and in this sensuous watercolour (below) we see what beauty looked like through the eyes of a gay man in Victorian England. He was fascinated by all kinds of religious ritual.

This picture by Simeon is so richly-coloured that we might think it's an oil painting, but it’s actually a watercolour. The ritual he shows here, the dispersion of incense in front of an altar, engages all our senses. The two men depicted here are surely male stunners, especially the young man on the right, with his dark eyes and his full lips.

Solomon has applied his colours thickly and he’s used lots of white, mixing it with the transparent watercolour to make bodycolour, also known as gouache.

He was only 23 when he made this artwork, but in 1873, when he was in his early thirties, a promising career came to a premature end when he was arrested and convicted for homosexuality. He ceased to exhibit.

His work was much admired in artistic and literary circles: he collaborated with the poet Algernon Swinburne (and wrote poetry himself), and Oscar Wilde owned works by him.

Solomon continued to draw and to paint, but it was very difficult for him to show his paintings in public ever again and he ended his life, tragically, in poverty at 65 in a London workhouse.

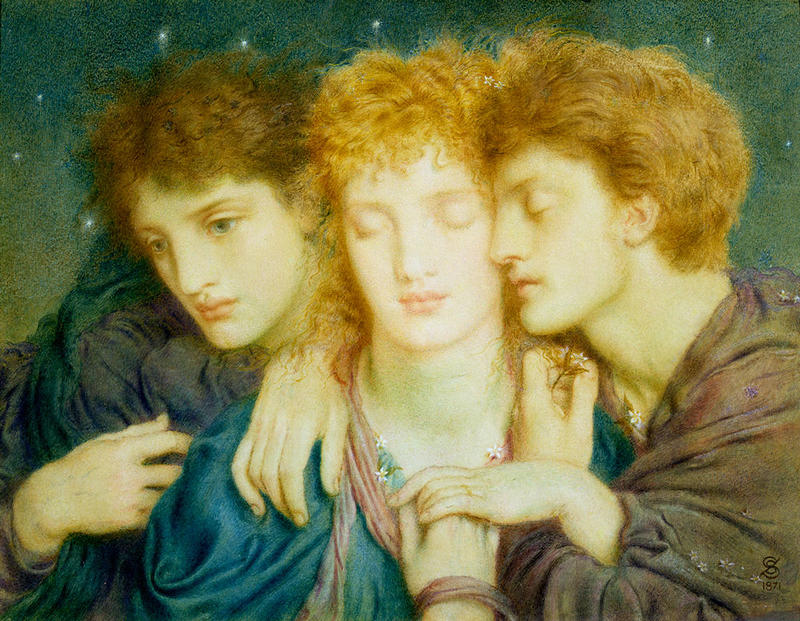

Marie Spartali Stillman (1844–1927)

Marie Spartali, later Stillman, was the daughter of Michael Spartali, a wealthy merchant who served as Greek consul-general in London from 1866 to 1879. Through her father she met the artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler, who introduced her to Dante Gabriel Rossetti in 1864.

She was famous for her statuesque appearance, and initially became one of the Pre-Raphaelite models and ‘stunners’. She was photographed by Julia Margaret Cameron and painted by Rossetti and Burne-Jones. But her ambition was to be an artist and so she trained with Ford Madox Brown, and from 1867 began exhibiting her own work regularly.

Marie herself became a painter of ‘stunners’ – many of her paintings feature beautiful young women, often depicted in Renaissance settings and with expressions that suggest thought or reverie. Her paintings are often feminist and enigmatic in theme.

In this celebrated Pre-Raphaelite watercolour, she presents herself as a young woman in Florence, with her lilies, rosary beads and prayer book, presumably thinking of her youthful life; this will come to an end if she decides to enter a convent, suggested by the building behind her. The subject echoes Charles Allston Collins’s painting ‘Convent Thoughts’, but the implications are completely different. Marie’s young woman is not simply an object for male admiration: she is thinking hard about her past – and her future.

In 1871 Marie married (against her family’s wishes) the American artist and journalist William James Stillman. As a result of his job as a foreign correspondent the couple made their home abroad, first in Florence and then in Rome. She continued to send her paintings back to England. Marie became good friends with Jane Morris and she often visited her in Kelmscott Manor after both lost their husbands.

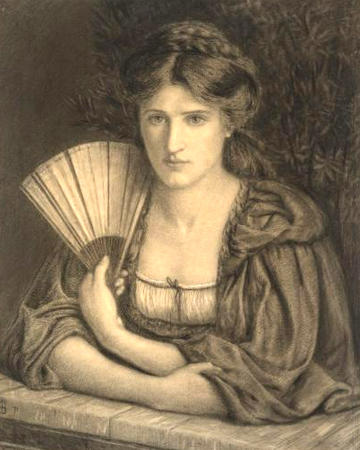

Violet Manners (1856–1937)

Violet Manners, Duchess of Rutland, was an artist and socialite. Born Violet Lindsay, she married Henry Manners in 1882. He inherited the title of Marquess of Granby in 1888, followed by that of Duke of Rutland in 1906.

Violet regularly exhibited her works at the Grosvenor Gallery, opened by her cousin Sir Coutts Lindsay in 1877.

From 1881 Violet also exhibited at the Royal Academy, showing her many pencil portraits of her friends – the group known as the ‘Souls’, which included the future Prime Minister, A. J. Balfour, and the Viceroy of India, George Curzon. This aristocratic social circle favoured refined intellectual and artistic pursuits. Known for her beauty, she was the subject of many paintings and drawings.

In this drawing (above left) of her by Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Coley Burne-Jones – a friend of the Manners family – Violet is portrayed as delicate and otherworldly, in keeping with her role as the hostess of the ‘Souls’. He has concentrated on her head and used soft pencil to suggest an otherworldliness and a fragility of character that suited this role. The drawing was given as a gift to Helen Mary Gaskell, with whom Burne-Jones had a close – but platonic – relationship.

Despite having no formal training, Violet was a very prolific artist and sculptor (self-portrait above right).

She is the sitter, in her role as artist, in a newly-acquired portrait by Sir James Jebusa Shannon (1862–1923), which is now on display in the Museum's Pre-Raphaelites gallery. Violet was painted on several occasions by the American-born artist J. J. Shannon, who was a leading portraitist in London at the time. This portrait is his most accomplished and fully captures Violet's fascinating personality, drawing attention to her haunting beauty. A glazed terracotta of the Virgin and Child frames her head, surrounded by a wreath of lemons.

Violet also published a selection of her many drawings in her Portraits of Men and Women in 1900.

Objectification of women?

Rossetti’s sister, the poet Christina Rossetti, saw something sinister in the Pre-Raphaelite obsession with female beauty.

Her poem ‘In An Artist’s Studio’ takes a male painter to task for objectifying his model, painting her, ‘Not as she is, but as she fills his dream’. Looking at some of these ‘stunners’ pictures of brooding, mysterious women (and men) today, we might also want to consider what the Pre-Raphaelite artists saw in themselves…

Many of the drawings and watercolours featured above were in the Ashmolean's Pre-Raphaelites 2022 exhibition. The Ashmolean has a significant collection of Pre-Raphaelite drawings and paintings, both behind the scenes and on display in the Pre-Raphaelites Gallery.