WOMEN POWER & THE ART OF MONEY

WOMEN POWER & THE ART OF MONEY

5-minute read

By Shailen Bhandare

Curator of the Ashmolean's major exhibition Money Talks: Art, Society and Power

With Sydney Smith

One of the highlights of the Ashmolean’s current exhibition, Money Talks: Art, Society & Power is the intentional emphasis on the role women have played in how art and money come together. It is seldomly recognised and mostly invisible.

In this article, the exhibition curator Shailen Bhandare, along with Sydney Smith, sheds light on the women who have designed money, and subverted and featured it in their artwork alongside the representations of women on coins and currency through history.

Art Nouveau Swiss banknote designs display in the Money Talks exhibition. © Hannah Pye / Ashmolean Museum

Women coin designers

Many classic 20th-century British coin designs were created by women designers. Madge Kitchener (1889–1974) was a trailblazer – her response to design a new 12-sided threepence coin for Edward VIII was not only ‘modern’ as the King wanted it, but also full of visual pun and wit.

Her choice of ‘three thrift flowers’ was unusual in replacing the high imagery of heraldry and allegory on past coins with a commonplace natural species. The number of flowers reflected the denomination and their name ‘thrift’ had a resonance with how people spend their money.

Three thrift flowers design by Madge Kitchener, proposed for King Edward VIII's brass threepence reverse, 1937 © Royal Mint Museum

For reasons not very well known, Madge Kitchener’s design was subsequently ‘reworked’ by a man – the sculptor designer, Percy Metcalfe. Edward VIII famously abdicated before being crowned in 1936 but the reworked ‘thruppence bit’ was adopted and issued for his successor George VI’s coins.

Kitchener’s legacy in creating what turned out to be a very practical, modern and popular coin design remains overshadowed by Metcalfe, who gets the credit for a design he reworked.

Following Madge Kitchener, many women artists such as Mary Gillick (1881–1965) and Mary Milner Dickens (1932–2019) have produced artwork for British coin designs.

Some of these, like Gillick’s head for the young Queen Elizabeth II, are considered as iconic because of their elegant appeal and clear execution.

Bronze penny, with Mary Gillick's ‘young bust’ of Queen Elizabeth II, 1964 © Ashmolean Museum

How women appear on coins and currency

Women often appear on modern money anonymously as representations and allegories. The imagery can be contextualised with popular artistic styles such as Art Nouveau and Art Deco.

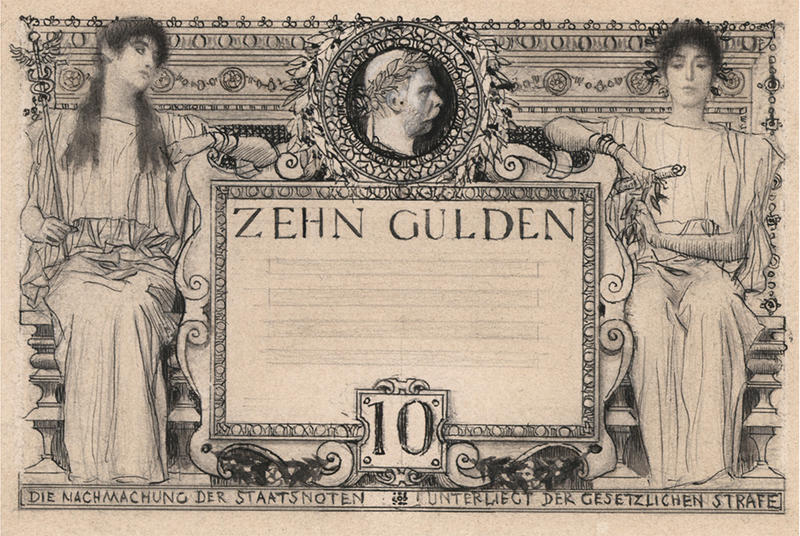

The engagement of Viennese Avant-Garde artists of the turn-of-century ‘Secessionist’ period with money design is hardly ever known. But it is a fascinating story of how tradition and innovation lock horns when it comes to designing money with its potential for circulating loaded messages.

Franz Matsch’s note artworks featuring an allegorical, sword-wielding woman are reminiscent of the German Historicist art school, comparable closely to his frescoes in the Burgtheater in Vienna.

The artwork for banknotes produced by a young Gustav Klimt pre-empts his Jugendstil genius with regard to its woman motifs. They are instantly recognisable with their dreamy eyes, fuzzy hair, loose faux-Classical dress and a rigid ‘Egyptian’ posture.

Sketch for a 10-gulden note (State Paper Money), Gustav Klimt, 1892 © Money Museum, Oesterreichische Nationalbank

Dreamy-eyed women also feature on banknote artworks proposed by Koloman Moser – the only artist who made it to a final product in circulation.

Draft artwork for 100-Crown note for the Austro-Hungarian Bank, Koloman Moser, 1900, watercolour, ink & graphite pencil on paper © Money Museum, Oesterreichische Nationalbank

The other Viennese artists, including Klimt, were rejected by the Imperial Austro-Hungarian Bank authorities because they had ‘very little appeal’!

Perhaps the most familiar woman to appear on money was the late Queen, Elizabeth II.

No less than 33 issuing authorities across the world have issued banknotes with her image and there are 31 different ‘monetary portraits’ showing her at different stages in her long life. Most are based on photographs taken by famous photographers which were re-engraved for use on money by artist-engravers.

Dorothy Wilding stands out amongst these as a pioneering 20th-century woman photographer. Stopped by her family from pursuing an acting or a painting career, she rebelliously declared, 'I’ll do it through the camera instead'. She began carving out a career as a top society portrait photographer, becoming the first woman official royal photographer for George VI’s coronation in 1937 and receiving a Royal Warrant in 1943.

Photograph of Queen Elizabeth II by Dorothy Wilding, 1952 © National Portrait Gallery, London

The royal connection and the striking simplicity of Wilding’s portraits meant she was also the first choice to photograph Queen Elizabeth II for the new coins, banknotes and stamps in 1953.

The Queen’s monetary portraits based on Wilding’s photographs are by far the most widespread, appearing on banknotes of more than 15 countries across the globe.

Specimen 10,000 dollars banknote of Malaya and British Borneo, 1953, © Ashmolean Museum

The honour of having one’s likeness grace a coin or a note is still largely reserved for men. Very few female figureheads adorn international currencies. Using money as a medium, some contemporary artists have reclaimed the banknote as a space to voice feminist political protest.

Defaced banknotes and women protestors

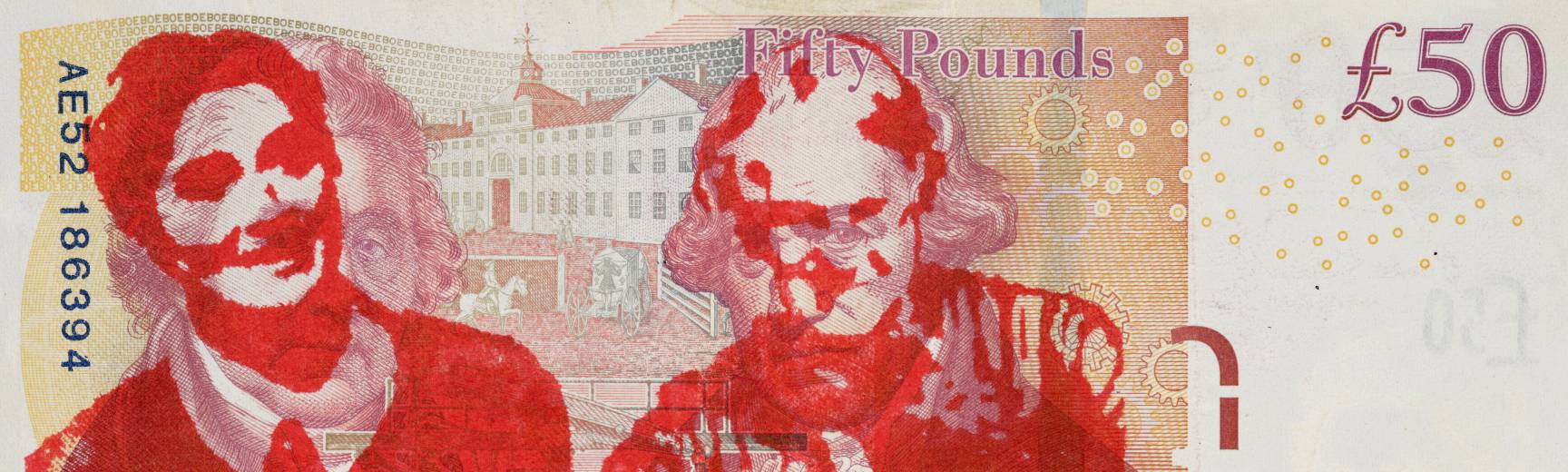

In the midst of a public outcry at social reformer Elizabeth Fry's (1780–1845) removal from the £5 note in 2016, the feminist artist Paula Stevens-Hoare created Notable Women, a series of artworks that explores currency as a site for protest.

In this series, Paula created portraits of British women considered notable according to the Bank of England's exacting criteria, and stamped them over male likenesses on current notes.

Her £10 note honours botanist and suffragette Marie Stopes (1880–1958); the £20 features the chemist and posthumous Nobel Prize laureate Rosalind Franklin (1920–58); and the £50 highlights the engineers Sarah Guppy (1770–1852) and Beatrice Shilling (1909–90).

Notable Women - Defaced British Bank Note, Paula Stevens Hoare, 2014, red & multicolour print on a £50 note (reverse), with Boulton and Watt over-stamped by portraits of engineers Sarah Guppy and Beatrice 'Tilly' Shilling © Paula Stevens-Hoare | Ashmolean Museum

Notable Women - Defaced British Bank Note, Paula Stevens Hoare, 2014, purple & multicolour print £20 note, with Adam Smith over-stamped by a portrait of chemist Rosalind Franklin (reverse) © Paula Stevens-Hoare | Ashmolean Museum

Notable Women - Defaced British Bank Note, Paula Stevens Hoare, 2014, brown & multicolour print £10 note, with Darwin over-stamped by a portrait of botanist Marie Stopes (reverse) © Paula Stevens-Hoare | Ashmolean Museum

It is interesting to note that Paula found no surviving images of Sarah Guppy, who patented the design for pilings that enabled Isambard Kingdom Brunel to construct his bridges. To make Guppy’s agency in Brunel’s success visible, Paula had to use an image of actor Kim Hicks who played Sarah Guppy in the 2006 one-woman-show, 'An Audience with Sarah Guppy'.

While exhibiting some of these defaced notes as framed artworks, Stevens-Hoare also put them back into circulation, continuing to spread a political message about gender representation as the money changes hands.

Money and gender, reclaiming equality and identity

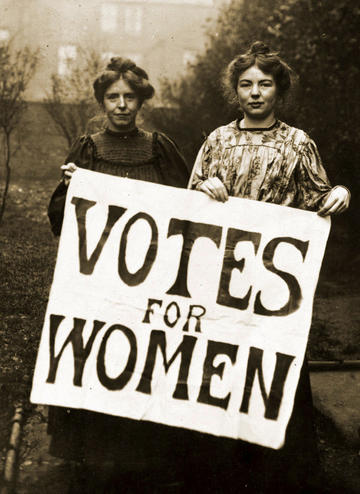

Campaigners and activists have sometimes used money as a medium, simply to circulate messages or to create artistic interventions, to push for gender equality. Defacing money was, and is illegal, and that in itself gives a subversive edge to such interventions. One of the earliest examples of these, and one that came to prominence when it was showcased in the British Museum’s 'A History of the World in 100 Objects' series, is the ‘Votes for Women’ penny.

Women's rights campaigners Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst holding a Votes for Women placard in about 1908. © Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

At the turn of the 20th century, women in Britain were still without the right to vote. An orchestrated campaign for female suffrage was under way with the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) adopting a policy of direct action, which included civil disobedience, debate, propaganda, and attacks on property.

Many militants were repeatedly imprisoned and some resorted to hunger strikes to highlight their cause. One strand of militant activity was the punching of pennies with the ‘Votes for Women’ slogan.

A handful of examples are known. Notably the treatment of coins showing Queen Victoria (1819–1901), as opposed to those of male monarchs, reveals something of the ideology of the suffrage movement. Coins of Edward VII or George V get the message stamped over their bust, while on coins of Victoria – perhaps out of female solidarity – the message is stamped across the figure of Britannia instead.

Queen Victoria, bronze penny, 1897, stamped ‘VOTES FOR WOMEN’ on reverse © Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

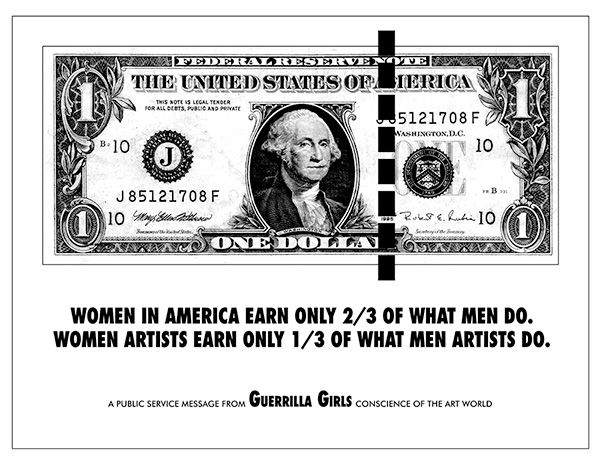

The concept of altering money to add a message to it carries a powerful resonance and has been used by artists and satirists to highlight many inequalities in society.

The ‘Guerilla Girls’ deploy a one-dollar bill – with a man, George Washington, staring out of – as a template to make a statement about the gender pay gap, emblazoning it with a slogan ‘Women in America earn only 2/3 of what men do’. A broken line, curiously mimicking the silver ‘security thread’ on many banknotes, appears two-thirds of the span of the dollar bill.

Women In America Earn Only 2/3 Of What Men Do, Guerrilla Girls, 1985, Screenprint on paper, Tate © Guerilla Girls

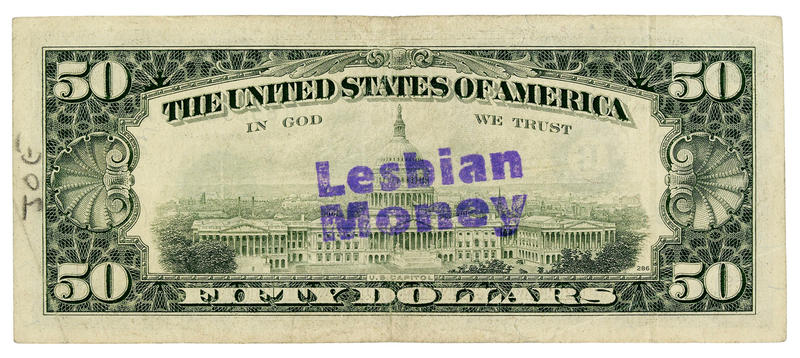

In the heyday of the gay and lesbian movement, notes stamped ‘Lesbian Money’ and ‘Queer Cash’ in ink became instruments of ‘financial self-identification’ for the LGBTQ community, underlining the potential importance of queer economy, commonly known as the ‘pink economy’.

$50 US banknote countermarked with the words ‘Lesbian Money’ © Ashmolean Museum

Read more about queering currency in our web article.

Money Dress: the fabric of female territory

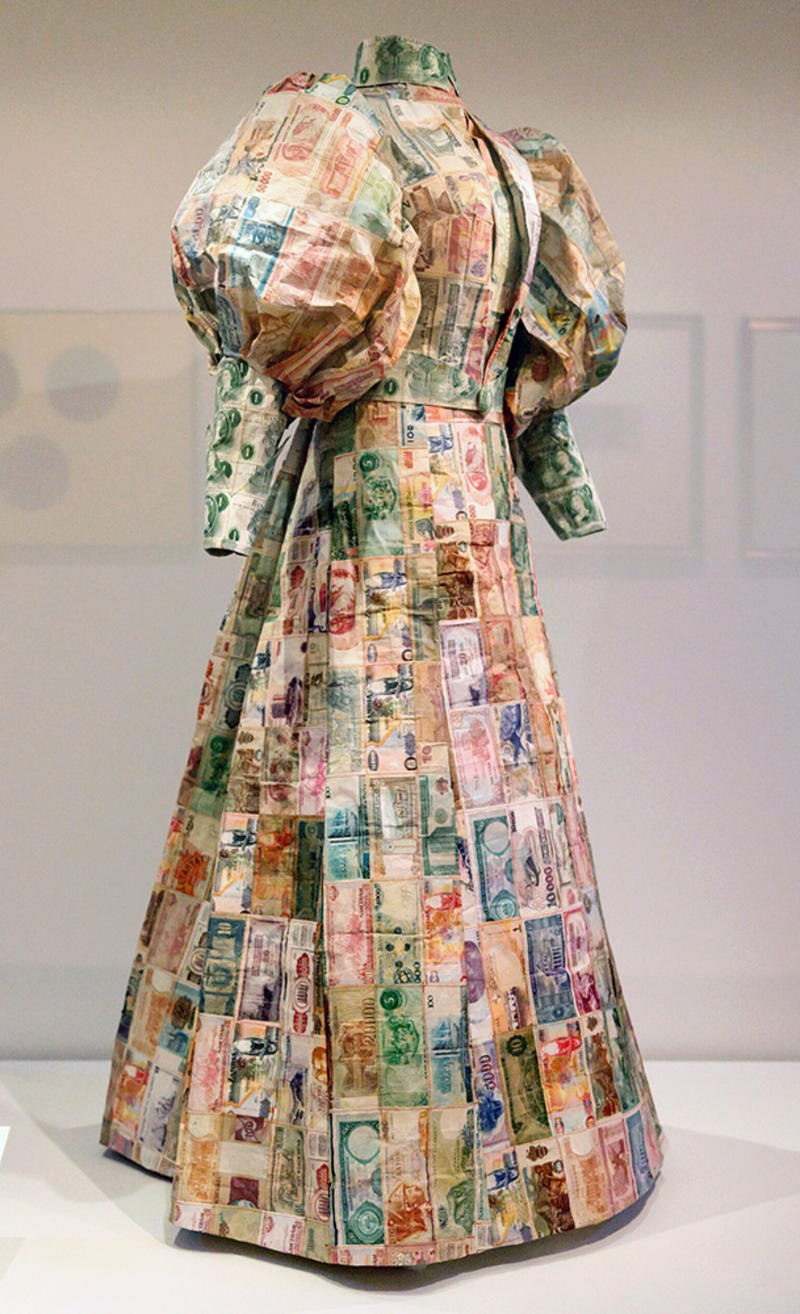

The lead image on the posters for the Ashmolean's Money Talks exhibition is the sculpture Money Dress by artist Susan Stockwell. Stockwell often uses international currencies in her work, which traces contemporary feminist and decolonial politics through material histories.

Money Dress, according to the artist, is ‘based on the idea of female territory and power being enabled by economic independence’ and honours late 19th to early 20th-century women explorers like Catherine Routledge (1866–1935), Isabella Bird (1831–1904) and in particular, Mary Henrietta Kingsley (1862–1900).

Susan Stockwell's Money Dress sculpture in the Money Talks exhibition © Susan Stockwell

The artist Susan Stockwell next to her Money Dress at the Money Talks exhibition preview © Hannah Pye / Ashmolean Museum

Victorian explorer Mary Kingsley © Public domain via Wikimedia

The sculpture was made while Stockwell was an Artist in Residence at the Royal Geographic Society (RGS) in 2010, drawing on the Society's extensive archives.

Mary Kingsley, to whom the artist pays her tribute, was a late Victorian ethnographer who used her inheritance to travel alone extensively. Kingsley achieved fame for her book 'Travels in West Africa' and became a controversial figure for her anti-proselytising views.

Susan’s original intention was that the whole dress would be made from currency featuring female figureheads – however they are still prohibitively rare! Susan therefore made the collars, cuffs and belt from money featuring female figureheads.

Money Dress collar, bodice, belt and cuffs detail, Susan Stockwell © Susan Stockwell

The rest of the dress is made from money with male figureheads on, but they are turned inwards so one can only see their backs. The piece is based on the idea of female ‘territory’ and power being enabled by economic independence.

Modern money, representing nation states and the political geography of the world, becomes an excellent medium to make such a creative comment.